A Global Health and Economic Crisis: The UN's Urgent Warning on Heat Stress and Workers

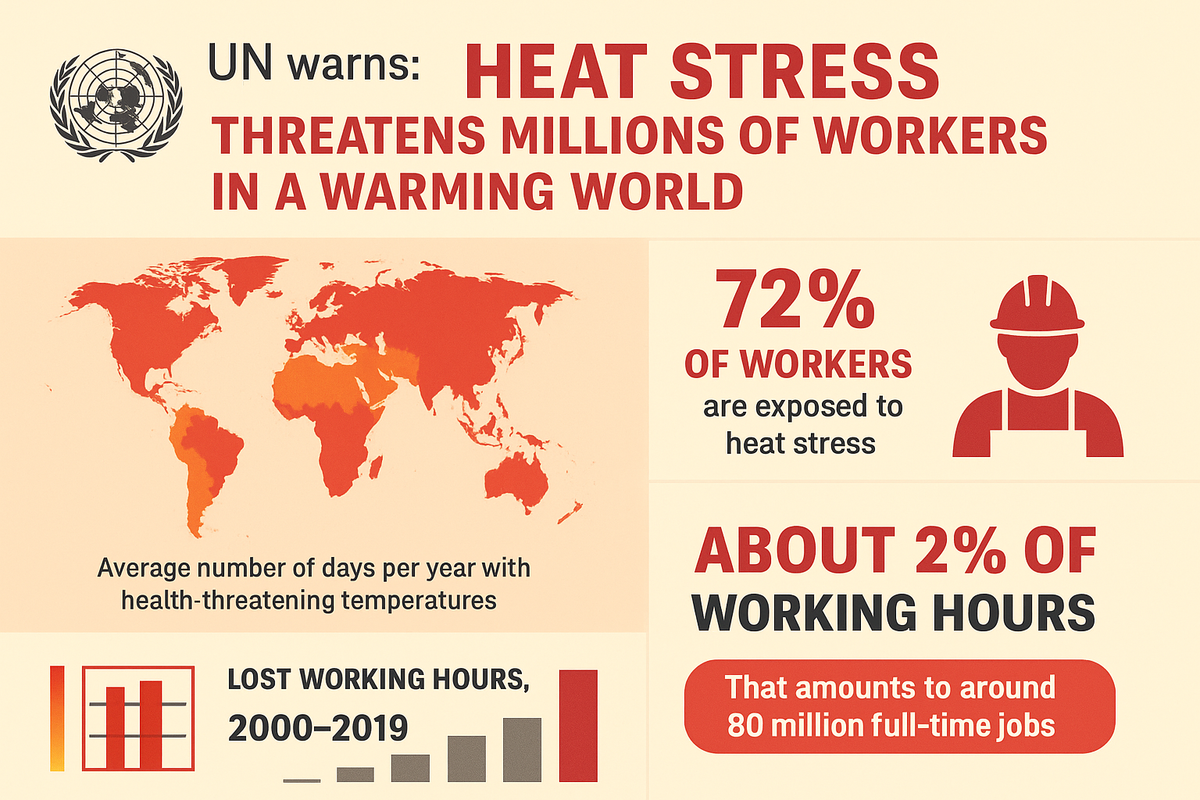

The UN's new report sounds the alarm on a deepening crisis: extreme heat threatens billions of workers, causing massive productivity loss and disproportionately harming low-income and migrant communities.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

GENEVA, August 22, 2025

The stark findings of a new joint report, "Climate Change and Workplace Heat Stress," released by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), serve as a definitive and urgent call to action. With 2024 confirmed as the hottest year on record, the report details how rising global temperatures are not merely an environmental concern but a profound and immediate threat to the global workforce, public health, and economic stability. It’s a sobering reality check that the world of work is already on the front lines of the climate crisis, and the consequences are dire.

The report, which draws on decades of cumulative research, highlights an escalating crisis that has long simmered in the background. It finds that over 2.4 billion workers, representing more than 70% of the world's workforce, are exposed to excessive heat, a number that has been steadily increasing. This exposure is directly linked to an estimated 22.85 million occupational injuries each year and nearly 19,000 fatalities annually. The message is clear: heat stress is an "invisible killer" that is already eroding human dignity, productivity, and the very foundations of the global economy.

A Historical Timeline of a Mounting Threat

The UN’s report is not a sudden revelation but a culmination of years of mounting evidence that has been largely ignored. To understand the scale of the current crisis, it's crucial to trace the trajectory of how we got here.

- 1970s-1990s: The Early Scientific Recognition. Initial research in this period began to identify the physiological impacts of heat on the human body, particularly for manual laborers. Studies focused on heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and the direct correlation between high temperatures and a decrease in physical work capacity. However, these were largely academic inquiries, and the issue remained a niche concern for occupational health specialists.

- 2000s: The Economic Wake-Up Call. As global temperatures began their accelerating climb, economists started to quantify the financial toll of heat stress. A 2009 study by the ILO, for instance, first introduced the concept of "lost working hours" due to heat. It revealed that as temperatures rise, workers' ability to perform strenuous tasks declines, leading to a direct drop in productivity and a corresponding loss in GDP, particularly in heat-vulnerable economies.

- 2010s: The Era of Escalating Heatwaves. The last decade saw an undeniable increase in the frequency, intensity, and duration of heatwaves. Events like the 2010 Russian heatwave and a series of record-breaking summers in Europe, North America, and Asia brought the issue into mainstream consciousness. The focus expanded from the tropics to include regions previously considered temperate. This is when the term "urban heat island" became common, highlighting how cities trap and amplify heat, making indoor and outdoor work increasingly hazardous.

- 2020s: The Global Reckoning. The period from 2020 to 2025 has been a turning point. With 2024 now confirmed as the hottest year, the effects are no longer abstract. Heat-related deaths among workers are on the rise globally. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has previously estimated that by 2030, a 1.5°C temperature rise could lead to the loss of 80 million full-time jobs due to heat stress. The latest WHO/WMO report builds on these findings, warning that this figure could be a conservative estimate if no mitigating action is taken. This is no longer a future threat; it is an active, worsening crisis that is already claiming lives and crippling economies.

The Human Cost: Disproportionate Impacts on Labor Migration and Vulnerable Workers

The UN report highlights a grim reality: the burden of heat stress is not shared equally. It falls most heavily on those with the least power and fewest resources.

The Perilous Journey of Climate Migrants: As agricultural lands become unworkable and outdoor work in traditional industries becomes untenable, heat is a major driver of climate migration. Workers move from rural areas to cities, often crossing borders in search of more stable work. This migration, however, often leads to what the report calls a "heat trap." Migrants, especially those without legal documentation, are forced into the most strenuous and dangerous jobs, such as construction, waste management, and informal street vending, which offer little to no protection from the sun. These workers are frequently paid by the day, meaning lost work hours due to heat are a direct and immediate hit to their already precarious earnings.

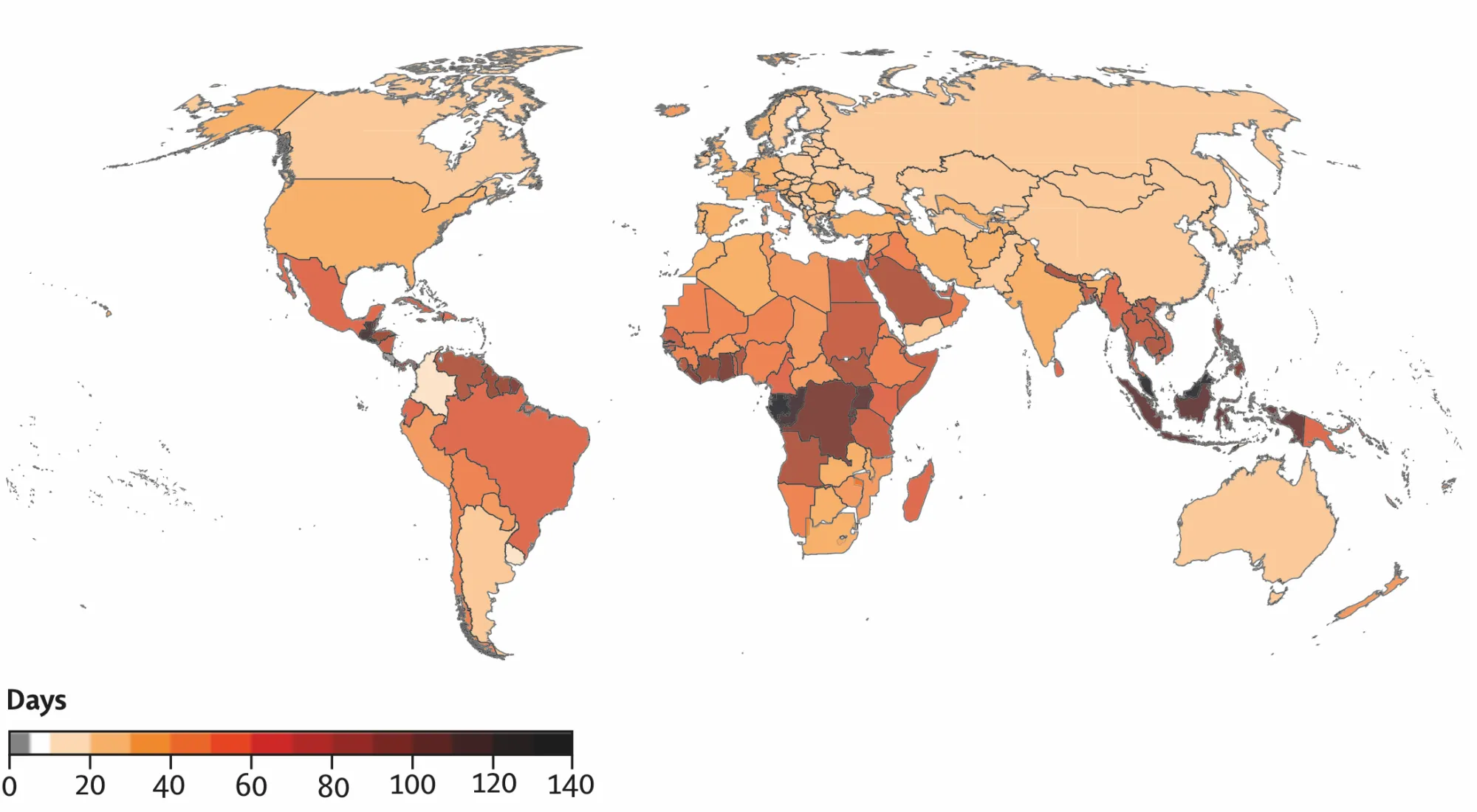

The Economic Squeeze on Low-Income Countries: The report estimates that by 2030, the global economy could lose the equivalent of $2.4 trillion USD a year from heat-related productivity loss. This is a staggering figure, but the impact is geographically concentrated. Developing nations in South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America—regions with a large proportion of their workforce in agriculture and construction—will bear the brunt of these losses. In these countries, the lack of robust social safety nets, healthcare access, and cooling infrastructure means workers are not only more exposed but also less able to recover from the physical and financial shock of heat stress. For instance, in West Africa and South-East Asia, productivity losses could be equivalent to 5% of working hours by the end of the decade.

This vulnerability is compounded by the fact that many of these workers are in the informal economy, with no access to social security or health insurance. As Dr. Jeremy Farrar, WHO Assistant Director-General, states, "Heat stress is already harming the health and livelihoods of billions of workers, especially in the most vulnerable communities. This new guidance offers practical, evidence-based solutions to protect lives, reduce inequality, and build more resilient workforces in a warming world."

On the Front Lines: Sectors Facing the Highest Risks

The UN report breaks down the risks by sector, painting a clear picture of where the crisis is most acute.

- Agriculture (The Most Exposed): With an estimated 940 million people employed globally, agriculture is the sector most vulnerable to heat stress. The work is almost entirely outdoors, physically demanding, and often performed in direct sunlight. The report projects that agriculture will account for 60% of all global working hours lost to heat stress by 2030. Lost productivity in this sector not only impacts individual livelihoods but threatens global food security.

- Construction (A High-Risk Environment): Construction workers are exposed to a double threat: high temperatures and intense physical labor. The report notes that construction will be "severely impacted," with an estimated 19% of global working hours lost in the sector by the end of the decade. This includes not just outdoor building sites but also workers in poorly ventilated indoor spaces. The combination of cognitive impairment from heat and the operation of heavy machinery makes this a particularly dangerous environment, leading to a higher risk of accidents and injuries.

- Manufacturing (The Indoor Heat Trap): While often thought of as an indoor activity, manufacturing is also a high-risk sector. Factories, particularly in developing countries, are often poorly ventilated and lack adequate cooling systems. The combination of ambient heat and the heat generated by machinery can create "heat islands" within the building itself. This leads to reduced productivity, increased human error on assembly lines, and long-term health issues for workers.

Solutions on the Horizon: From Policy to Technology

While the report details the scale of the problem, it also provides a roadmap for solutions, emphasizing that a multi-pronged approach is essential.

Policy and Regulatory Action: The report’s primary recommendation is for governments to formalize heat as an occupational hazard and implement comprehensive national heat action plans. This includes:

- Mandatory Rest Breaks: Establishing legal requirements for paid rest breaks in shaded, cool areas based on the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) index, which accounts for temperature, humidity, and sun exposure.

- Early Warning Systems: Creating and disseminating heat early warning systems to the public and, specifically, to employers and workers in at-risk sectors.

- Protective Legislation: Amending national labor laws to explicitly include protections against heat stress, ensuring workers have the right to refuse work in unsafe conditions without fear of reprisal.

- Investing in Public Infrastructure: Expanding access to public cooling centers, providing shade structures in urban areas, and investing in green infrastructure that naturally cools cities.

Innovative Workplace Adaptations: Companies have a critical role to play in adopting and implementing practical solutions.

- Low-Tech Solutions: These include staggered work schedules to avoid peak heat hours (e.g., a "siesta" model), providing unlimited access to cool water and electrolyte drinks, and encouraging workers to wear lightweight, loose-fitting clothing.

- High-Tech Solutions: The report highlights a growing market for personal protective equipment (PPE) designed to mitigate heat, such as cooling vests and neck wraps. For industrial settings, innovations in passive cooling technologies, smart ventilation systems, and reflective roofing materials are gaining traction.

Case Study: Singapore's Proactive Approach. The report points to Singapore as a successful model. The country's Ministry of Manpower has implemented a robust set of heat stress measures for outdoor work, including mandating the use of the WBGT index to determine work-rest cycles. The regulations require employers to provide rest areas, hydration, and training on heat-related illness. This proactive approach has significantly reduced heat-related incidents and serves as a blueprint for other nations.

The Next Frontier: How Technology Might Reshape the Future of Work

The UN report also speculates on how emerging technologies like AI, remote work, and automation could fundamentally alter the landscape of heat-related risks.

Remote Work as a Partial Solution: The pandemic-era shift to remote work has shown that for many information-based jobs, the office is no longer a necessity. This has the potential to remove millions of workers from exposure to both urban heat islands and poorly regulated indoor environments. However, this solution is limited to a privileged segment of the global workforce and offers no protection for the majority of manual laborers.

The Rise of Automation: In the long run, automation and robotics could be a game-changer. Jobs that are currently highly susceptible to heat stress—such as farming, construction, and manufacturing assembly—could be increasingly handled by machines. Automated vehicles and drones could perform tasks like crop spraying or site surveying during peak heat hours. AI-powered robots could operate in high-temperature industrial settings, removing human workers from direct exposure.

AI as a Predictive and Safety Tool: AI is already being developed to provide real-time, hyper-localized heat risk assessments. These systems can combine weather data with physiological monitoring to predict when a worker is at risk of heat stress, triggering an alert for a mandatory break. AI can also be used to optimize work schedules to minimize exposure and to analyze historical data to identify and rectify hazardous work conditions.

The challenge, of course, is ensuring that these technological shifts are managed equitably. The transition to automation must be paired with investment in reskilling and social safety nets to prevent mass unemployment and the creation of a new, technologically-displaced class of workers.

A New Social Contract for a Hotter World

The UN’s report is a critical document that forces us to re-evaluate our relationship with work in a warming world. It argues that the very idea of a "safe working environment" must be fundamentally redefined to include climate hazards. The path forward demands a new social contract, one that acknowledges that the health and well-being of the workforce are not externalities to be managed but core assets to be protected.

The UN’s report is not a prediction of a distant future; it is a diagnosis of a present crisis. Its recommendations are a clear mandate for immediate action. Companies, governments, and international organizations must collaborate to:

- Adopt and Enforce Legal Standards: Make heat stress an official occupational hazard with clear, enforceable legal thresholds for safe working conditions.

- Invest in Adaptation: Redirect funds and resources into both low-tech and high-tech solutions to make workplaces cooler and safer.

- Prioritize the Most Vulnerable: Develop targeted policies that protect informal and migrant workers, ensuring they have access to the same rights and protections as formal employees.

The Deliberation Room: Questions for Our Future

- How can we create a globally enforceable framework for worker protection from heat stress, given the wide economic disparities between countries and the varied nature of work?

- If automation and AI are the ultimate solution to heat stress, what moral and economic responsibilities do wealthy nations and tech companies have to help developing economies navigate this transition without leaving a generation of workers behind?

Sources

The information presented is based on reports from the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), and the International Labour Organization (ILO), alongside various academic studies and governmental analyses on occupational safety and climate change.