A Planetary Crossroads: Inside the UN Plastics Treaty Negotiations and What’s at Stake for the Planet

As the final round of negotiations for a landmark UN plastics treaty concludes in Geneva, the world watches to see if nations can agree on a legally binding instrument to curb plastic pollution.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

GENEVA, August 14, 2025

The Evidence: A Tsunami of Data

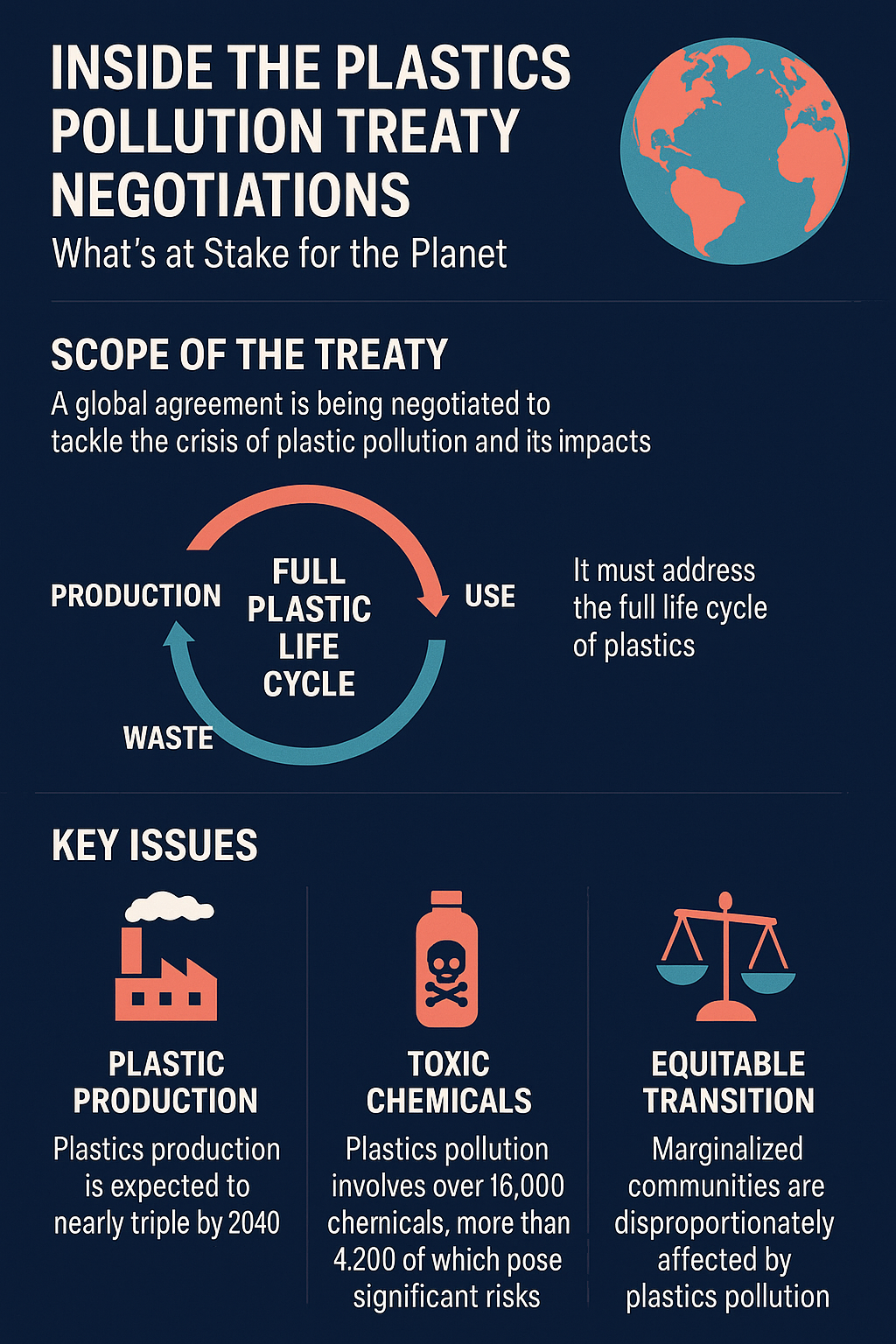

The crisis we face is not abstract; it is quantified by an ever-growing deluge of data. Global plastic production has surged from 2 million metric tons in 1950 to an estimated 460 million metric tons annually as of 2024. If current trends continue, this figure could more than double to 884 million metric tons by 2050. The vast majority of this plastic is not recycled. Only about 9% of all plastic ever produced has been recycled, with a mere 1% recycled more than once. The rest ends up in landfills or, more alarmingly, contaminates our environment.

Each year, between 19 and 23 million metric tons of plastic waste leak into our aquatic ecosystems, an amount equivalent to dumping two thousand garbage trucks full of plastic into our oceans, rivers, and lakes every single day. The consequences are far-reaching. At least 1,400 species of marine and terrestrial wildlife are directly affected by plastic pollution, suffering injury, entanglement, and death.

Beyond the visible waste, there is a hidden danger. A recent report published in the medical journal The Lancet underscores that plastics are a “grave, growing, and under-recognized danger to human and planetary health.” Plastics contain over 16,000 chemicals, many of which are known to be hazardous, including endocrine disruptors like phthalates and carcinogens. The report estimates that the health-related economic losses from plastic pollution exceed $1.5 trillion annually. The problem is intrinsically linked to the climate crisis: the full lifecycle of plastics, from extraction to disposal, accounted for 4.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2015, a number projected to grow significantly as the fossil fuel industry increasingly pivots to plastic production.

A Timeline of Tectonic Shifts

The road to a global plastics treaty began with a landmark resolution in March 2022 at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in Nairobi, Kenya. The resolution, adopted by 175 nations, called for the creation of a legally binding instrument to address the entire lifecycle of plastics. An Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was established with the ambitious goal of completing the treaty by the end of 2024.

- INC-1 (November 2022, Punta del Este, Uruguay): The inaugural session established the scope of the negotiations, with a broad consensus on the need for a comprehensive, lifecycle-based approach.

- INC-2 (June 2023, Paris, France): Delegates, representing a majority of countries, called for the development of a "zero draft" of the treaty to serve as the basis for future talks.

- INC-3 (November 2023, Nairobi, Kenya): This session was marked by procedural delays and a clash over whether the treaty should address plastic production limits. Despite the gridlock, a comprehensive zero draft was ultimately produced.

- INC-4 (April 2024, Ottawa, Canada): While there was progress on measures to restrict problematic plastic products, the core issue of capping plastic production remained a significant point of contention.

- INC-5.1 (November-December 2024, Busan, Republic of Korea): The first part of the fifth session ended without a final deal, but it laid the groundwork for the current talks. The "Chair's text" was adopted as the basis for negotiations in Geneva.

- INC-5.2 (August 2025, Geneva, Switzerland): This is the final and most critical phase of the negotiations, where nations are attempting to finalize a legally binding treaty text. As of August 14, delegates are deep in the final hours of talks, with a new draft text having been released that, according to observers like WWF, "failed to live up to expectations."

The Sticking Points: A Global Tug-of-War

The final negotiations are a battle of wills between two opposing blocs of nations, each with a fundamentally different vision for the treaty. This division is not just about environmental policy; it's about economic development, national sovereignty, and the future of the fossil fuel industry.

The High Ambition Coalition (HAC), a group of over 85 nations including the European Union, Rwanda, Norway, and Panama, is pushing for a strong, legally binding treaty that addresses the root cause of the problem. Their core demands are:

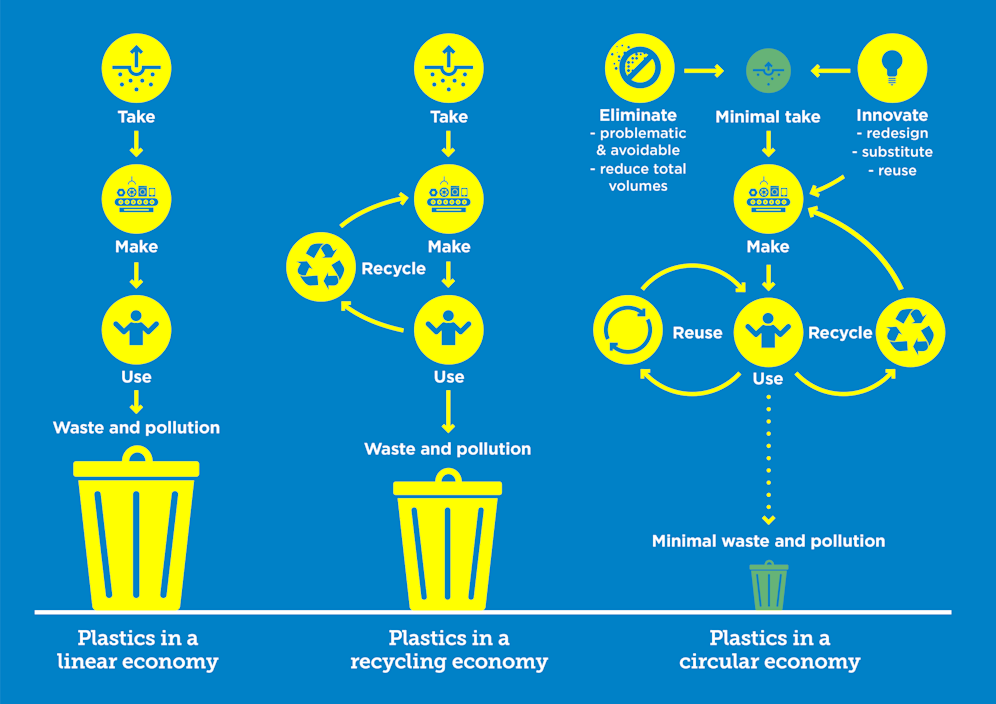

- Mandatory Production Cuts: The HAC argues that the world cannot recycle or manage its way out of the crisis. They are advocating for legally binding caps on the production of virgin plastic polymers to "turn off the tap."

- Harmonized Global Rules: They seek common, global rules to phase out problematic and avoidable plastics, such as many single-use items, and to regulate the thousands of hazardous chemicals used in plastic production.

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR): They propose a strong EPR framework, making companies financially responsible for the full lifecycle of their products, from design to end-of-life management.

The Like-Minded Countries (LMC), which includes major oil and petrochemical-producing nations like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, and China, along with other countries, takes a different view. This bloc is backed by powerful industry lobbyists who have been a visible presence at the talks. Their position is that the treaty should be a voluntary framework focused solely on improving waste management and recycling infrastructure. They vehemently oppose any language that would restrict plastic production, arguing that it would stifle economic growth and that the problem is not with the material itself, but with its mismanagement.

The influence of the fossil fuel and petrochemical industries is undeniable. A recent Greenpeace report revealed that since the treaty process began in 2022, seven major fossil fuel and petrochemical companies—Dow, ExxonMobil, BASF, Chevron Phillips, Shell, SABIC, and INEOS—have produced enough plastic to fill an estimated 6.3 million rubbish trucks. These companies are actively lobbying to weaken the treaty, as plastics represent a critical new market for them as the world transitions away from fossil fuels for energy.

A Ripple Effect: Impact on Industry and Markets

A robust, legally binding treaty with production caps would send shockwaves through global markets. The petrochemical industry, which has been betting on plastics to sustain its profitability, would face a fundamental challenge to its business model. The treaty would force manufacturers and packaging companies to innovate and invest heavily in sustainable alternatives, such as biodegradable materials, and to build out a truly circular economy based on reuse and refill systems. This is not just an environmental imperative; it is an economic opportunity, potentially unlocking a new wave of sustainable investment.

Conversely, a weak, voluntary treaty focused only on waste management would be a victory for the plastics and fossil fuel industries. It would allow for business as usual, with a continued surge in plastic production, and would shift the burden of cleanup to developing nations and local governments. This could exacerbate existing inequalities, as many communities in the Global South already bear the brunt of plastic waste from wealthier countries.

Enforcement and the Role of International Law

Enforcing an international environmental treaty is a complex undertaking. The UN plastics treaty would likely be governed by a system of national reporting, peer review, and a non-compliance mechanism. Such mechanisms often focus on providing technical and financial assistance to countries struggling to meet their commitments, rather than imposing punitive sanctions. However, the treaty's power lies in its ability to create a common standard and a global consensus. As witnessed with other environmental agreements, a strong, clear treaty text can be a powerful tool to hold states and corporations accountable, even without a heavy-handed enforcement body. The treaty could also create a financial mechanism to help developing nations build the necessary infrastructure for a circular economy, thereby addressing a major barrier to implementation.

A Defining Moment for Biodiversity and Human Health

The treaty's ultimate success will be judged by its impact on biodiversity and human health. Plastic waste, from macro-litter to microscopic particles, is a relentless force of destruction. Microplastics, now found in every corner of the planet and even within the human body, can act as vectors for toxic chemicals, leading to a host of potential health problems. A strong treaty would protect biodiversity by setting ambitious goals to reduce plastic leakage into ecosystems and by banning harmful chemicals from the plastic lifecycle. It would also empower nations to create policies that prioritize public health over industrial profits. A treaty that fails to address production and chemical content would be a missed opportunity, leaving the door open for the continued proliferation of a material that is literally choking the life out of our planet.

A Test of Global Will

As the delegates leave Geneva, the world is left with a stark reality: the future of our planet's health rests on the agreement they either forge or fail to reach. The negotiations have exposed the deep fault lines between a business-as-usual model that prioritizes profit and a new vision for a sustainable, circular economy. The final text will be a testament to whether nations can overcome short-term economic interests to act on a crisis of global proportions. The treaty, in its final form, will be more than a document; it will be a reflection of our collective courage and a blueprint for the kind of world we choose to leave for future generations.

Our Call to Action

How can individual citizens and local communities apply pressure to ensure their governments support the most ambitious version of the plastics treaty, even after the final text is agreed upon? What are the ethical responsibilities of corporations, particularly in the fossil fuel and plastics industries, to voluntarily shift away from business-as-usual, regardless of the final treaty's provisions?

Sources

UN Environment Programme (UNEP), The Guardian, Breakfreefromplastic, The Lancet, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Greenpeace, Our World in Data, and official INC meeting reports.