China Offers Cash for Babies: Can Financial Incentives Reverse Its Population Decline?

Explore China's new cash-for-babies program—regional subsidies, free preschool, milk vouchers—and compare with global fertility policies. Will financial incentives work?

BEIJING, July 4, 2025

In a significant shift, China is now financially encouraging its citizens to have more children. After many years of population control, the world’s second-largest economy faces an urgent demographic challenge, one that cash incentives alone may not solve. As national birthrates fall and economic pressures rise, the crucial question isn’t whether China can afford to offer more support—it’s whether Chinese families are willing to accept it.

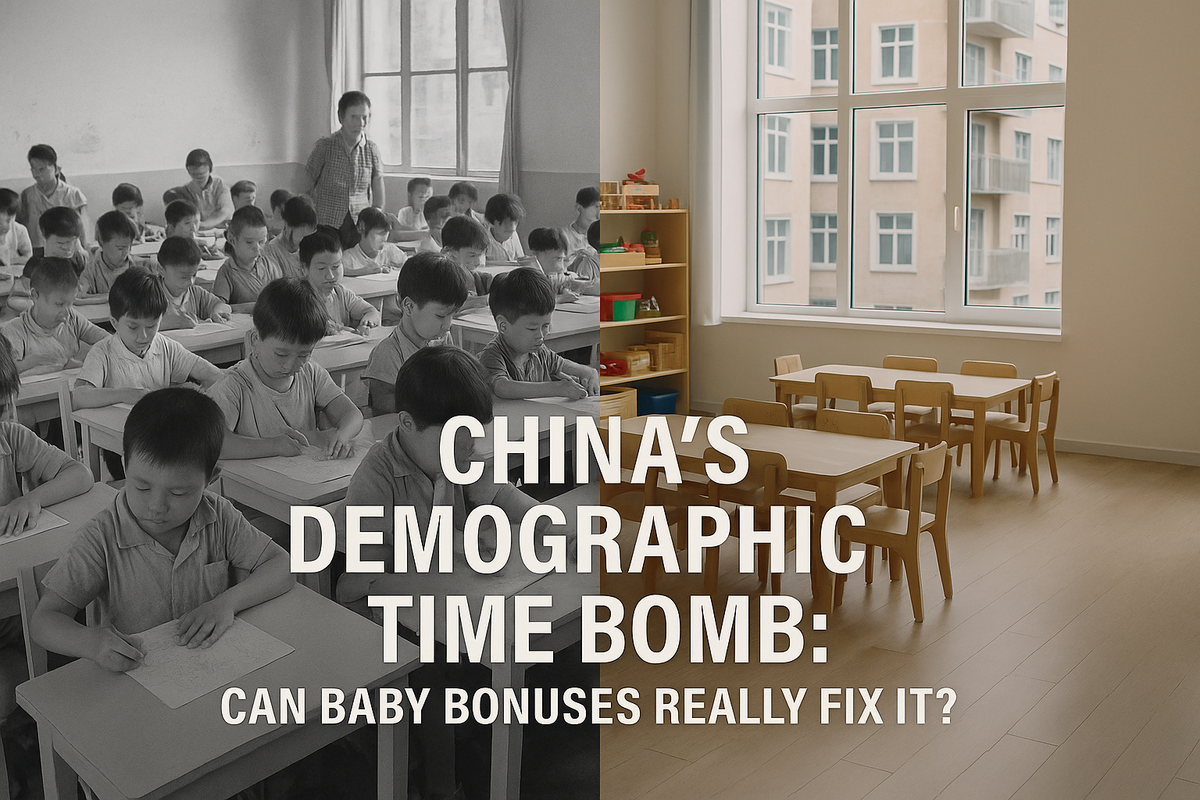

A Nation Facing a Shrinking Future

China's population started to decline in 2022, and the data since then has painted a bleak picture. The country’s Total Fertility Rate (TFR) dropped to just 1.09 in 2023, far below the 2.1 replacement rate. This decline coincides with rapid aging—by 2050, more than 40% of China’s population will be over 60.

The effects are not just numbers on a page. A smaller labor force leads to slower economic growth, strained pension systems, and possible challenges in defense and innovation. The population issue is no longer a long-term worry; it is now an economic emergency.

The Incentive Wave: From Milk Vouchers to Major Payouts

To address this population decline, China's central and local governments are trying various financial incentives. Some cities, like Hohhot in Inner Mongolia, offer up to ¥100,000 (~$14,000) per child over ten years. Others, like Tianmen in Hubei, combine monthly childcare payments with housing subsidies and priority school enrollment.

In Tengzhou city, Shandong, free preschool programs are expanding, and milk vouchers are available for families with young children. These initiatives, while differing by region, reflect a nationwide urgency to support falling fertility rates financially. In some rural counties, such as Xingxian in Shanxi, parents receive one-time payments between ¥2,000 and ¥8,000 for each child, depending on birth order.

These programs aim to reduce the financial burden of raising children and encourage young couples to start families sooner. However, the implementation and impact of these measures vary across the country.

“It’s not just about money. Social attitudes and gender expectations must shift.” — Yao Lu, Sociologist at Columbia University

Mixed Reactions on the Ground

While some cities have seen a slight increase in birth rates, especially those with generous local benefits, many urban couples remain cautious. A 2025 survey by Tsinghua University found that two-thirds of women aged 22–35 said they had no plans for children in the next five years. Even among men, over half of unmarried respondents felt that financial incentives wouldn’t influence their decision to marry or start a family.

For many young Chinese, the expense of raising a child is just one part of the equation. Job pressures, high housing costs, the challenges of balancing work and family life, and societal expectations—especially on women—make parenthood less appealing.

One 29-year-old advertising executive from Guangzhou, who chose to remain anonymous, summed it up:

“It’s not about the money. It’s about freedom, time, and whether I can be a good parent without giving up my entire identity.”

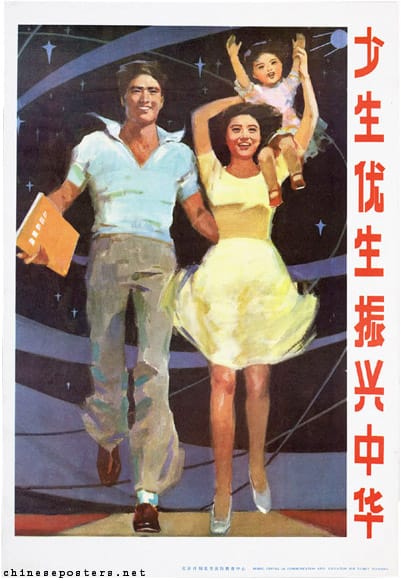

The Policy Pendulum: From Restrictions to Rewards

Just a decade ago, the Chinese government strictly enforced the one-child policy, often using fines, forced abortions, and intense surveillance. That history is hard to forget. After years of telling families to have fewer children, the same government now urges them to have more.

In 2016, China lifted the one-child policy and introduced a two-child limit, followed by a three-child policy in 2021. But the anticipated increase in birth rates never happened. In fact, birth rates continued to drop. The current set of financial incentives marks the most forceful policy change yet, showing not only economic concern but also political anxiety about the country's long-term future.

Unlike earlier campaigns, today's policies include no penalties for unwed parents in some provinces and even promote flexible family structures. For a society still influenced by Confucian values, this marks a significant shift—and possibly a necessary one.

Lessons from Around the World

China is not alone in facing this issue. Countries like Japan, South Korea, Hungary, and Singapore are also dealing with falling birth rates, and their different policy approaches provide insights into what might work—or not.

In South Korea, families receive substantial cash bonuses and free fertility treatments, yet the fertility rate has dropped to a record low of 0.72. Hungary has had some success with tax exemptions and housing support, while Singapore’s “baby bonus” program has only slightly stabilized birth rates.

These examples show that while financial incentives can help, they often don't suffice without supportive cultural and structural reforms. Attitudes toward marriage, gender expectations, and parenting significantly influence whether people choose to have children at all.

| Country | TFR (2024) | Major Incentives | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 1.3 | Paid parental leave, childcare subsidies | Stable but low |

| South Korea | 0.72 | $10K baby cash, IVF funding | Still declining |

| Hungary | 1.5 | Tax-free status for mothers with 4+ children | Moderate success |

| Singapore | 1.1 | Baby Bonus, grants, housing priority | Modest stabilization |

| China | 1.09 | Regional cash programs, free milk, schooling | Local upticks, national plateau |

Culture, Cost, and Career: Why Cash Isn’t Everything

Despite the government’s efforts, the underlying social barriers to having children remain. Professional success often conflicts with family planning. In China’s tough job market, the notorious “996” work culture—working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week—leaves little time or energy for parenthood.

Additionally, the imbalance in domestic responsibilities persists. Many women worry that having a child will derail their careers, especially with limited maternity support and a lack of affordable daycare. Fathers, on the other hand, are not always expected or encouraged to participate equally in caregiving.

These cultural realities, combined with rising living costs in cities, mean that money alone may not be enough to change the trend.

As one social media user on Weibo commented: “The government wants babies, but employers want robots. Until we have rights at work and daycare that don't cost a salary, it’s all talk.”

Economic Stakes and Strategic Ambitions

The stakes of China's demographic crisis reach beyond family planning. A shrinking labor force threatens the nation's status as a manufacturing giant and slows down domestic consumption. The Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security estimates that China could face a shortfall of 30 million workers by 2035.

This shortage is already noticeable in high-tech sectors like semiconductors and artificial intelligence, both vital for China’s strategic competition with the U.S. The country also requires more young talent to spur innovation, support military readiness, and maintain global influence.

In this way, the baby bonus is not merely a social policy—it represents an effort to secure China's competitive edge globally.

“Cash subsidies may slow the decline, but they won’t reverse it without deeper structural reform.” — Liang Jianzhang, Economist and Demographics Expert

What Could Actually Work: A Broader Blueprint

Experts believe that instead of isolated cash incentives, China needs a broader, family-friendly system. National childcare programs, longer maternity and paternity leave, housing help, and gender equality in parenting could create conditions where young people genuinely want to raise families.

Cultural reform is just as crucial. This means reducing stigma around single parenthood, encouraging men to take active roles in parenting, and redefining success, not just through professional achievements but also in terms of quality of life.

Countries like Sweden and France have shown that when people feel secure and supported, they're more likely to start families. China’s significant economic capability suggests these changes are feasible, but they will require political commitment and long-term dedication.

What the Future Holds: More Than Just Babies

While some regional successes, like those in Tianmen, indicate that birth rates can rise, they are still exceptions. Whether these improvements can be replicated nationwide is uncertain.

The way forward may not depend on subsidies alone. It could involve creating a society where raising a family is seen as a rewarding choice—not a burden—where work-life balance is real, gender equality is established, and education and healthcare are available for everyone.

Only then can China hope to reverse its demographic decline and forge a more sustainable, inclusive future.

A Nation at a Crossroads: Between Hope and Hesitation

The challenge for China is not just how to increase its birthrate but how to transform a society so that people want to have children. In this sense, financial incentives are not the final answer—they serve as a signal, a call, and a starting point.

The future of China’s families—and its economy—depends not only on nursery cribs but also on how young people view their futures, their freedom, and their roles in a changing world.

Let’s Talk: What Would Make You Start a Family?

Are cash bonuses enough to encourage parenthood? Or should governments focus on deeper changes, like affordable childcare, flexible work schedules, and support systems?

What policy would make you feel confident about starting or growing a family today?

We’d love to hear your thoughts.

Sources

- Reuters – Coverage on China’s financial incentives and demographic strategies: reuters.com

- South China Morning Post (SCMP) – Case study of Tianmen's 17% birth rate increase post-incentives: scmp.com

- Time Magazine – Analysis on cultural and financial limitations of fertility incentives: time.com

- China Daily & Xinhua News – Official reports on government policies, local subsidies, and early childhood programs: chinadaily.com.cn, english.news.cn

- Wall Street Journal (WSJ) – Visual coverage of urban parenting and response to incentive programs: wsj.com

- ChinesePosters.net – Archival images from the one-child policy era showing propaganda posters: chineseposters.net

- BMC Public Health – Academic analysis on the effectiveness of local policies and regional disparities: bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com

- Tsinghua University Survey (2025) – Cited for public sentiment statistics on parenthood (referenced in local press summaries, non-public dataset).