Dark Side of Vulnerability: How Japan’s 'Twitter Killer' Exploited Suicidal Victims Online

How Japan’s “Twitter Killer” used mental health hashtags to lure suicidal individuals into deadly traps—and what this case tells us about the dangers of unchecked online vulnerability.

TOKYO, June 27, 2025

When Loneliness Meets Predation

In the quiet, hyperconnected corridors of social media, loneliness often echoes the loudest. Japan, a country known for its technological innovation and disciplined society, hides a painful reality—its mental health crisis. When vulnerability goes unchecked in digital spaces, it becomes prey for the darkest minds.

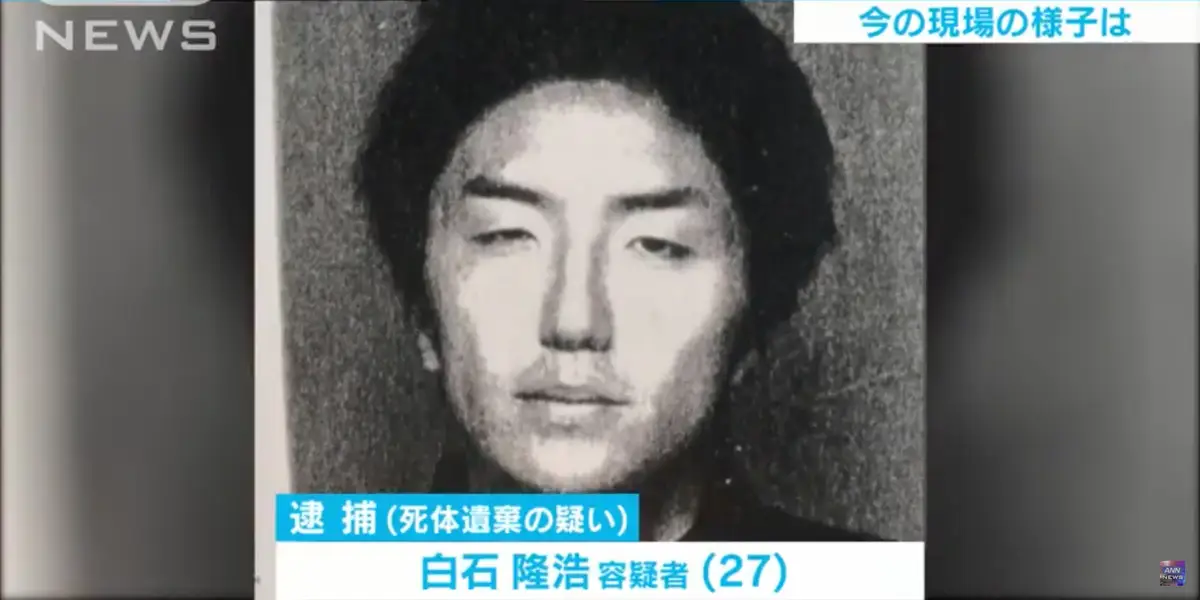

Between August and October 2017, a 27-year-old man named Takahiro Shiraishi, later called the "Twitter Killer," used Twitter to find and murder nine people, most of whom were looking for an end to their lives. His method was chillingly modern: he searched for users tweeting about suicide, reached out with compassion, and then lured them to their deaths.

This blog investigates how online predators exploit emotionally vulnerable people, what this reveals about Japan’s mental health system, the role of social media platforms, and what this case warns us about in the digital age.

Digital Hunting Ground: How the 'Twitter Killer' Operated

In a country where suicide has long held cultural and societal weight, social media platforms have quietly become safe spaces for those in despair. For many, especially young adults, Twitter is a way to express feelings they can’t share in real life. It was within this online world that Shiraishi thrived.

Under the Twitter handle @hangingpro, Shiraishi presented himself as someone who could “help those who truly want to die.” He openly promised to accompany people in suicide pacts, telling his victims:

“Let’s die together. You won’t be alone.”

By using hashtags like #自殺募集 (suicide recruitment) and #死にたい (I want to die), Shiraishi targeted users actively seeking companionship in death. He approached them privately, gained their trust through empathy, and invited them to meet at his apartment in Zama, a city in Kanagawa Prefecture.

But there were no suicide pacts. He murdered eight women and one man, dismembered their bodies, and stored the remains in cooling boxes. It was only when the brother of one missing victim tracked down the conversations and contacted the police that the horror was revealed.

Mental Health in Japan: A Silent Epidemic

To fully grasp this tragedy, we must look beyond the crime and examine the flaws in Japan’s mental health system.

Japan has historically struggled with high suicide rates. In 2017—the same year as the murders—20,000 people took their lives, making it one of the highest rates in the developed world. Suicide is the leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 39.

While Japan has made commendable efforts in the last decade to bring these numbers down, barriers still exist:

- Stigma: Talking about depression or suicidal thoughts is taboo in many families and workplaces.

- Limited Resources: Mental health support is often underfunded, with a lack of licensed therapists and crisis centers.

- Workplace Pressure: The culture of overwork (karōshi) continues to create a perfect storm for stress-related breakdowns.

These realities drive many to anonymous platforms like Twitter, where they seek empathy, guidance, or simply someone to listen. Tragically, these spaces can also be where the most vulnerable are targeted and exploited.

The Psychological Manipulation Behind the Crimes

According to court records from the Tokyo District Court, Shiraishi’s victims were not physically forced into his apartment. Instead, they were emotionally manipulated, believing he was the only one who understood their pain.

This behavior fits a troubling pattern often seen in online predators. Their manipulation techniques include:

- Mirroring Pain: Predators echo their victim’s emotions to build trust.

- Promising Escape: They offer a solution, often an escape from life itself.

- Isolating the Victim: They discourage victims from sharing their feelings with others.

- Seizing Control: They lure victims to places where they have physical power.

During his trial, Shiraishi claimed: “I killed them without their consent, but I didn’t think I’d be punished.”

This statement reflects a disconnection from moral consequences—a hallmark of psychopathy.

The Role of Twitter: Platform or Enabler?

One of the most challenging questions in this case is: Could this have been prevented?

At the time of the murders, Twitter Japan had no effective moderation policy concerning suicide-related content in Japanese. Despite millions of users, the platform lacked Japanese-speaking moderators and did not flag or restrict hashtags like #死にたい (I want to die), which Shiraishi used frequently.

Even his username “@hangingpro”—a disturbing reference to suicide—was not marked as inappropriate by automated filters or human reviews.

Only after the murders became a global story did Twitter revise its policies. In 2018, it promised to work with Japanese NGOs and introduced tools for detecting harmful content in local languages.

Yet, implementation is still inconsistent. While Twitter now offers mental health support links and hides certain hashtags, its reactive moderation leaves enough gaps for tragedies to happen again.

Data Snapshot: Suicide & Digital Behavior in Japan

,

- Google Trends Data (2015–2023): Search volume for “how to die painlessly” peaked in late 2017, the time of the murders.

- Suicide Prevention Helpline Use: Calls increased by 30% following the media coverage of the Twitter Killer case.

- Mental Health Tweets: Nearly 3.1 million Japanese tweets in 2021 included phrases such as "死にたい" ("I want to die").

These statistics reveal two key points: the scale of the crisis and the heavy reliance on platforms for emotional expression.

Legal Ramifications & Ethics of Surveillance

After Shiraishi’s sentencing, talks in the Diet (Japanese parliament) shifted toward improving online monitoring, especially of suicide-related content. Lawmakers proposed the following:

- Mandated Reporting by Social Media Platforms

- AI-based Suicide Risk Algorithms

- Government-Certified Crisis Bot Deployment

While these measures aim to prevent future tragedies, rights groups caution against the fine line between protection and surveillance.

The Japanese Civil Liberties Union stated: “We cannot replace mental health support with mass monitoring. Surveillance is not a substitute for empathy.”

The question remains: How do we create safer digital spaces without making them oppressive?

Similar Cases Worldwide: A Global Pattern

The Twitter Killer case, while shocking, is not unique. Around the world, predators have used online spaces to target vulnerable individuals:

- UK (2012): A man used suicide forums to encourage vulnerable users to take their lives.

- US (2021): A TikTok user posed as a therapist, gaining followers before exploiting their personal trauma stories.

- South Korea: The Nth Room Case revealed how women were blackmailed using mental health vulnerabilities.

These cases demonstrate a clear pattern: digital anonymity often protects predators more than victims.

What Happens Next? A Call for Platform Accountability & Empathy

After the Twitter Killer case came to light, Japan’s government took a multi-faceted approach:

- Increased Funding: Mental health services received a 30% budget increase in 2021.

- Youth Helplines: New 24/7 chat-based support centers were launched, especially for teens.

- AI Suicide Detection: LINE and Twitter now use algorithms to identify suicide risk in posted text and alert moderators.

However, experts argue that technology must complement, not replace, human care.

The Journal of Digital Ethics published a 2021 report concluding: “Algorithms can identify patterns. But they can’t respond with compassion. We need human-led mental health care infused with ethical tech design.”

Final Lens: Code, Compassion, and Consequence

The case of Takahiro Shiraishi is not just a story of crime. It reflects the failure of three connected systems:

- A society that stigmatizes emotional vulnerability

- A platform that allowed predation

- A digital culture that is not ready for compassion

In a world where suffering is now visible through tweets, hashtags, and search patterns, we are left wondering what safety truly looks like in this digital age.

As technology becomes better at reading our words, predicting our moods, and assessing our behaviors, the line between passive observation and ethical responsibility starts to blur. If platforms can detect signs that someone is contemplating suicide, should they take action?

Some people say yes. They believe platforms should intervene with trigger warnings, hotline prompts, or alerts to authorities. Others warn that such actions might lead to over-surveillance, false accusations, and invasion of personal privacy, especially in cultures where talking about mental health can already cause ostracization.

However, this debate is about more than just code and algorithms. It is not a tech issue; it’s a human one. Every distressed post deserves more than just impressions and metrics. It deserves attention, empathy, and, most importantly, action rooted in humanity.

So, where should the line be drawn?

Should digital platforms have a moral (or legal) responsibility to intervene in mental health crises? Could such actions save lives, or might they further isolate already-vulnerable users?

Sources

- Court ruling and policy: Tokyo District Court press release / Ministry of Justice (Japan), Reuters, CourtListener (translated judgment archive), Al Jazeera, ABC

- News analysis: Japan Times, NHK, BBC News Asia, Reuters Japan, The Guardian Global Dispatch, France‑24, Wikipedia, Nippon.com

- Psychology and digital ethics research: Journal of Cyberpsychology (JSTOR), Journal of Digital Ethics Vol. 22 (2021), Japanese Ministry of Health Suicide White Paper

- Platform and tech policy: Twitter Safety Blog (2018 Health Update), Google Trends analysis (suicide-related searches in Japan, 2015–2023), Wayback Machine archive of Shiraishi's Twitter account

- Media insights: ANN News / Japanese television broadcast, Business Insider, Japan Times, The Guardian / Kyodo via AFP

- Public sentiment: Tweets under hashtags #自殺募集 and #死にたい; Reddit threads in r/JapanLife and r/TrueCrime; Japanese NGO statements from Befrienders Tokyo and JCLU (Japanese Civil Liberties Union)