Demographic Decline: How Aging Populations Threaten Global Economic Stability

Investigative report on how demographic decline is unraveling the global economy. Explore case studies from Japan, South Korea, and Italy, analyzing the fiscal pressures of an aging population, the debate between immigration and automation, and China's role in reshaping global supply chains.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

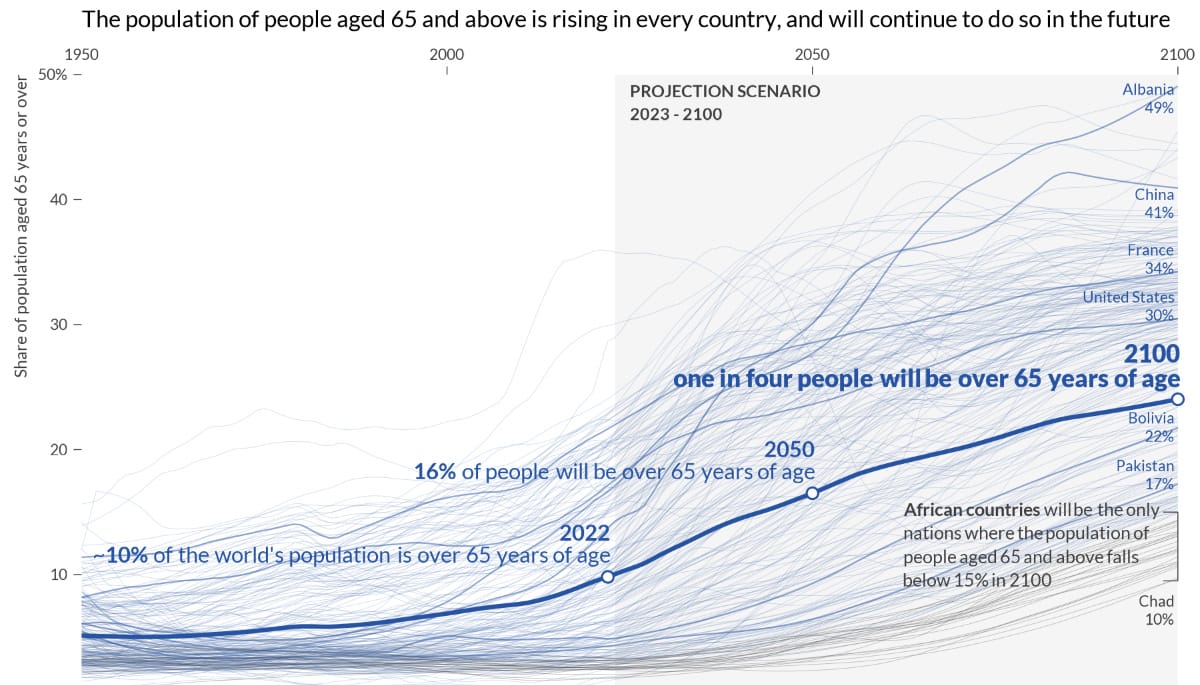

A demographic shift of historic proportions is underway, and its ripples are already being felt in boardrooms and government halls across the globe. For decades, the world's most developed nations relied on a robust, young workforce to drive innovation, fuel consumption, and pay for the social safety nets of their elders. But that model is broken. In countries that are the pillars of the global economy - from Tokyo to Berlin and Rome - the population is not just aging; it is shrinking, and the demographic pyramid is inverting. This quiet but powerful trend is creating a new era of economic headwinds, fiscal instability, and social tension, forcing a global reckoning with a future where growth is no longer a given. This report delves into the hard data and policy responses to this crisis, analyzing its cascading effects on labor, technology, and global power dynamics.

Anatomy of a Decline: The Data Behind the Crisis

The evidence for demographic decline is irrefutable and can be seen in the falling fertility rates of developed nations. The replacement rate, the number of births per woman needed to maintain a stable population, is 2.1. Today, many of the world's most influential economies are well below that number.

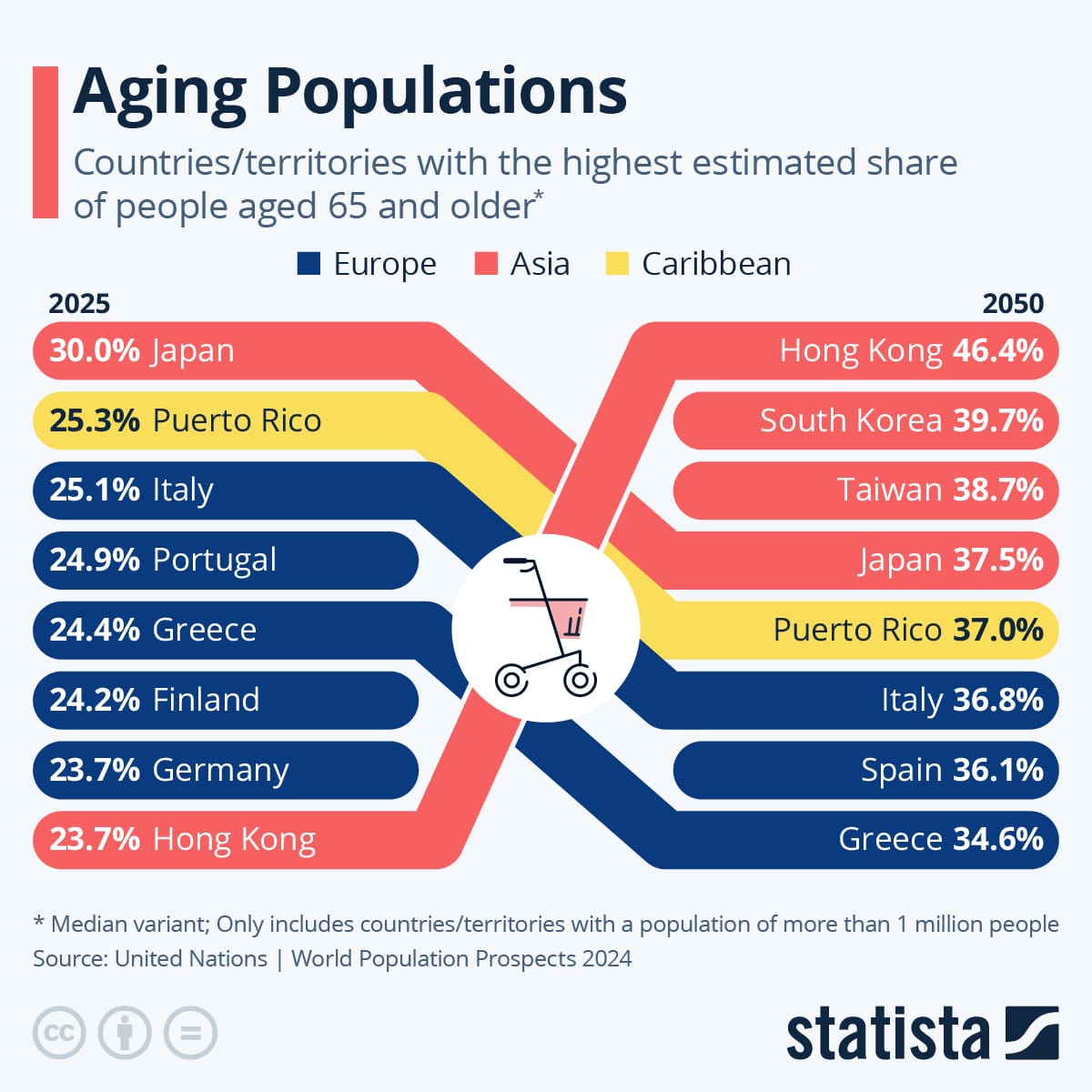

- Japan: The canary in the coal mine for this crisis, Japan's population has been in decline since its peak in 2008. The country's fertility rate has been consistently below the replacement level since the 1970s and is currently around 1.2. The country's National Institute of Population and Social Security Research projects that by 2060, a staggering 40% of the population will be 65 or older. This has led to a stagnant economy, with average annual wages barely increasing since 1990, a factor that is itself contributing to the cycle of low marriage and birth rates.

- South Korea: South Korea holds the dubious distinction of having the world's lowest fertility rate, plummeting to just 0.72 in 2023. Experts warn this rate could halve the nation's population in just 50 years. As a result, the country is already facing a severe labor crunch and increasing strain on its pension and social care systems, a phenomenon a demographics expert called a "headwind to potential growth."

- Italy: Italy, like many of its European counterparts, is on a similar path. The country's fertility rate is just 1.18, and its population is projected to shrink by over 13% by 2050. With one of the world's highest median ages, Italy is struggling to maintain its expansive public pension system, with a shrinking tax base trying to support a growing number of retirees.

This demographic reality is causing a significant increase in the old-age dependency ratio, the ratio of retirees to working-age people. This inversion puts immense pressure on a nation's ability to generate the tax revenue needed to support its social safety nets, from healthcare to pensions. As the European Central Bank has noted, this "poses a burden on fiscal policy, through upward pressure on pension spending and adversely affecting the tax bases."

The Strategic Response: Immigration vs. Automation

In the face of these headwinds, governments are wrestling with two primary and often polarizing solutions: immigration and technological innovation.

Immigration: The Human Answer.. From a purely economic standpoint, immigration is seen as the most direct solution. Young, working-age immigrants can immediately boost the labor force, increase tax revenues, and, in some cases, help lift birth rates. The IMF has consistently argued that "only net immigration can ensure population stability or growth in the aging advanced economies."

However, this is not just an economic issue; it is a profound social and political one. Japan, for example, has historically resisted large-scale immigration, with foreign-born residents making up only around 3% of the population. The debate over opening borders is fraught with cultural and social concerns, often leading to a political deadlock. Many countries, particularly in Europe, have seen the rise of populist movements fueled by anti-immigration sentiment, making it difficult for governments to implement the policies that economists argue are necessary.

Automation: The Technological Lifeline. As a political alternative to immigration, many aging countries are turning to technology. The hope is that automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence can fill the labor void, making a smaller workforce more productive.

Japan is a prime example of this strategy. With a severe shortage of caregivers, the country is at the forefront of developing robots to assist the elderly. From companion robots to automated lifting devices, technology is being deployed to provide care without an expansive human workforce. Similarly, China, facing its own rapidly aging population and rising wages, is investing heavily in industrial robotics to automate its manufacturing sector and maintain its position as a global production hub.

While automation offers a potential solution, it is not without its own set of challenges. The International Monetary Fund has found that increased robot density in Japan's manufacturing sector has been associated with both greater productivity and gains in employment and wages. However, the widespread adoption of AI and robotics also raises concerns about job displacement, particularly for low-skilled workers, and the potential for a widening gap between those who own the technology and those whose jobs are replaced by it.

The Ripple Effect: Housing, Youth Migration, and China's Role

The demographic crisis extends far beyond a simple labor shortage. Its effects are felt in unexpected ways, from the cost of housing to the very structure of global trade.

Housing Market Paradox: Conventional wisdom might suggest that a shrinking population would lead to lower housing costs, but the reality is far more complex. While a decrease in population growth can put downward pressure on prices in some areas, other factors can drive prices up and exacerbate inequality. In many aging societies, wealth is concentrated in the hands of the older generation, and the rise of single-person households can actually increase demand for smaller living spaces in urban areas, keeping prices elevated. At the same time, the hollowing out of rural areas can leave behind abandoned homes, creating a stark contrast between a handful of vibrant cities and a vast, depopulated countryside.

The Compounding Problem of "Brain Drain": Another compounding factor is the out-migration of young, skilled workers from aging countries. Facing limited opportunities, low wages, and the fiscal burden of supporting a growing elderly population, younger generations in countries like Italy and other European nations are increasingly moving abroad for better career prospects. This "brain drain" deprives their home countries of the very talent and innovation needed to navigate the demographic crisis, creating a vicious cycle of decline.

China's Pivot and Global Supply Chains: Perhaps the most significant global consequence is the changing role of China. For decades, China's massive, young workforce fueled its rise as the world's factory. Now, with the one-child policy a thing of the past, the country is facing its own rapidly aging population and a shrinking workforce. This is a primary driver behind a global shift in manufacturing, as companies look to diversify their supply chains to younger, more labor-rich countries like Vietnam and India. China, in turn, is attempting to pivot from a low-cost manufacturing model to a high-tech, consumer-driven economy. How successfully it navigates this transition will have profound implications for global trade, investment, and the future of every multinational corporation.

What Happens Next?

The demographic decline is not a single problem but a complex web of interconnected crises. There are no easy answers, only difficult choices.

Governments will be forced to make politically painful decisions. This will likely include raising retirement ages, reforming public pension schemes, and finding creative ways to fund healthcare for a growing number of non-working citizens. We will see a greater embrace of technology in every aspect of life, from automated taxis to robot caregivers, but this will raise new questions about social equity and the future of work. The debate over immigration will intensify, as the economic necessity for new workers clashes with deeply held cultural identities. The ultimate success or failure of these societies will depend on their ability to find a new social contract that is both economically viable and culturally sustainable.

The Rise of the "Periphery"

For decades, the global economic narrative has been dominated by a handful of established powers in North America, Europe, and Asia. But as these core nations age and shrink, the new engine of global growth may emerge from the periphery. Younger, more demographically dynamic economies in places like Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa, which once served as labor pools for the developed world, are now poised to become the new centers of manufacturing, consumption, and innovation. The era of a few dominant economic players may be ending, giving way to a more decentralized and multipolar global economy driven by the demographic vitality of these emerging regions. This isn't just an economic shift—it's a reshaping of the very geography of global power.

What do you think?

How can societies effectively manage the fiscal strain of an aging population without creating an insurmountable financial burden for younger generations? To what extent can technological solutions like AI and robotics truly replace the human element in professions like healthcare and education, and what are the ethical implications of this shift?

Sources

- McKinsey Global Institute

- International Monetary Fund (IMF)

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS), Japan

- World Economic Forum (WEF)

- The World Bank

- Various News and Academic Sources

- Visualcapitalist

- Statista

.