How the ICC’s Taliban Arrest Warrants Could Reshape International Human Rights Law

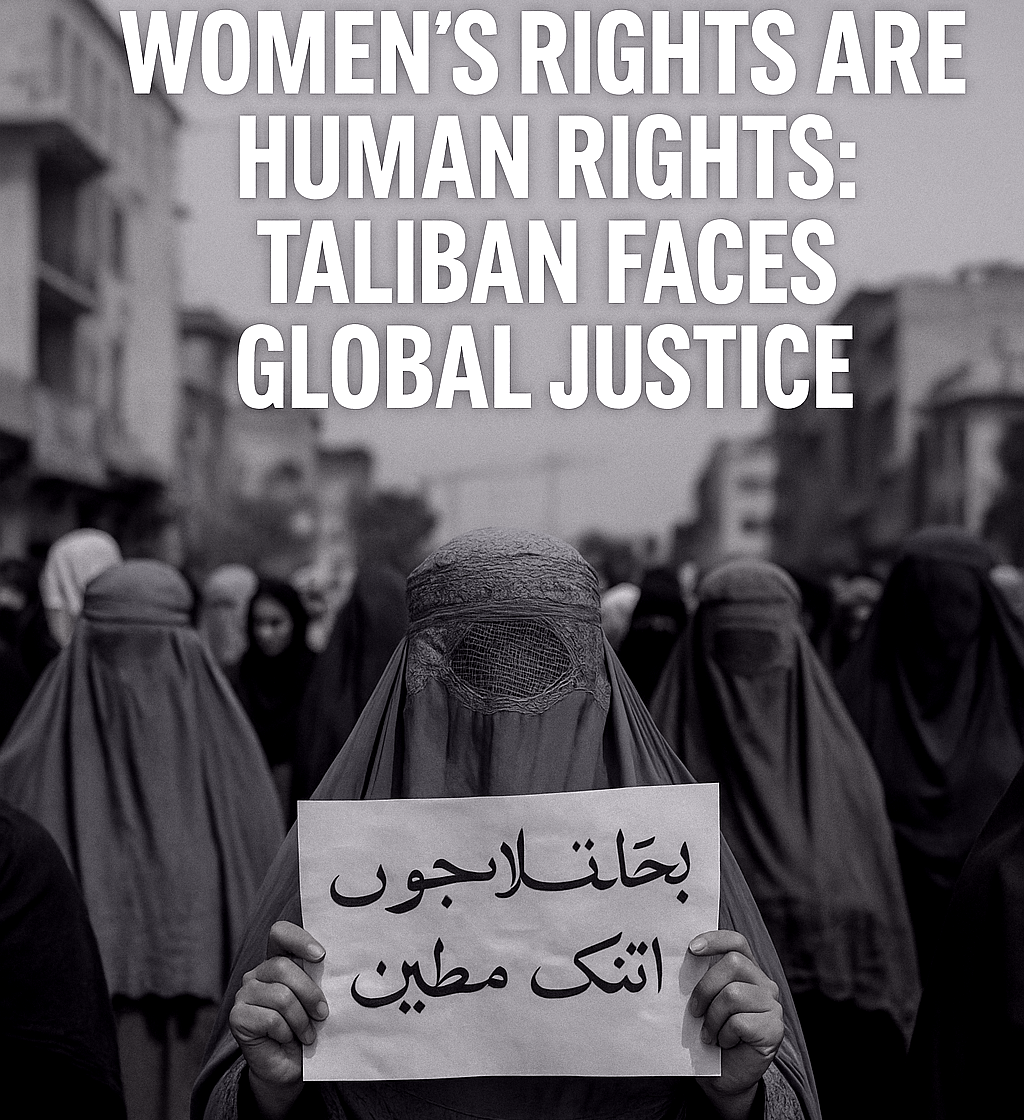

The ICC has issued arrest warrants for Taliban leaders over gender-based oppression, marking a historic first in treating women's persecution as a crime against humanity. Can this reshape international law, or is it symbolic?

THE HAGUE, July 8, 2025

A Game-Changer in International Legal Norms

On January 23, 2025, the International Criminal Court (ICC) took an unprecedented step by issuing arrest warrants for Taliban Supreme Leader Haibatullah Akhundzada and Chief Justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani. They are charged with the crime against humanity of persecution based on gender under Article 7(1)(h) of the Rome Statute. This is the first time the ICC has targeted an active government not for mass killings or sexual violence, but for the systematic oppression of women and gender non-conforming individuals. Legal experts are calling it a historic shift in accountability.

Amnesty International’s Secretary-General Agnès Callamard described this as an important step toward justice for Afghan women, girls, and LGBTQI persons. She added that it advances the recognition of gender apartheid as a crime under international law.

The ICC’s Legal Grounds & Evidence

The ICC’s application presents a strong legal foundation:

- Systematic persecution of women and girls, which includes bans on education beyond grade 6, restrictions on employment, limits on movement, healthcare constraints, and enforced male guardianship.

- Evidence based on Taliban decrees, witness testimonies, expert reports, and digital documentation, such as classroom footage and banned edicts.

- The ICC connects these crimes to state policy, meeting the Rome Statute’s criteria for persecution as a crime against humanity.

Legal scholar Agila Radhakrishnan of the Atlantic Council labels it a landmark moment:

“This is the first time a case has been built around crimes of gender persecution.”

Adding moral weight, Malala Yousafzai and UN envoy Gordon Brown have endorsed the ICC’s case as reflecting gender apartheid.

Reframing Oppression as a Crime

Traditionally, international criminal law required graphic violence—murder, rape, torture—for prosecution. The ICC’s new approach changes that: Systematic denial of rights, such as education, employment, and mobility, now qualifies as crimes if part of a policy. This aligns with the court’s expanded gender justice rulings, evident in earlier cases like Ongwen.

The Taliban’s more than 80 restrictive edicts since August 2021 clarify their gender bias, similar to apartheid systems.

International Reactions: Hope vs. Skepticism

The response has been sharply divided:

Praise

- UN Women calls it a breakthrough in recognizing women’s dignity.

- Amnesty International is pushing for formal recognition of gender apartheid as a crime.

- Afghan activists, such as Shukria Barakzai and Zahra Haqparast, call it long-awaited vindication.

Criticism & Doubt

- The Taliban dismisses the warrants as baseless and biased.

- Strategic analysts warn that the warrants may be symbolic without enforcement.

- Regional governments, including Pakistan and China, consider it interventionist or political.

Enforcement: Symbolic or Substantive?

The Legal Power of the Warrants

These warrants are legally binding in member states of the Rome Statute. Other countries and airlines have been officially notified not to transport the accused. Visa bans, asset freezes, and diplomatic bans may follow, isolating Taliban leaders.

Real-World Limitations

Afghanistan is not a signatory to the ICC, so there is no power to extradite. Taliban leaders remain in the country, avoiding travel. Regional non-cooperation with Iran, Pakistan, Russia, and China hinders apprehension. Critics argue the action might remain symbolic rather than judicial. Yet, legal experts maintain that symbolic accountability is important.

Still, legal experts say symbolic accountability matters. Reed Brody notes:

“It helps to stigmatise what is happening in Afghanistan… people engaging with the Taliban are on notice.”

Precedents & Legal Evolution

New Terrain for War Crimes

The ICC’s Al-Hassan case in Mali, focusing on religious persecution, lays a foundation for broader prosecutions related to non-violent atrocities. Legal scholars, including those at the Atlantic Council and UNC Law, see this as a step toward recognizing gender apartheid as a crime.

The current ICC move indicates a shift; legal change is possible, even without immediate enforcement.

Voices from the Ground

Afghan women in exile and underground schools highlight the importance of visibility. Secret schools still operate in Kabul, teaching girls who are banned from classrooms. Youth activists say the ICC’s action brings recognition and hope. However, restrictions are tightening in Afghanistan: women are barred from ministries, NGOs, hospitals, and many professions.

Timing & Strategy: Why Now?

This legal action is not random; it coincides with rising repression since August 2021, marked by school closures, public floggings, and LGBTQI+ crackdowns. It follows intensified advocacy from the Afghan diaspora and international allies demanding justice. There is momentum from the ICC’s gender justice strategy, especially after the Mali verdict. The application was submitted just before a UN General Assembly session, pushing global governance discussions to address the issue.

Between Symbolism and Precedent

This ICC case does more than target Taliban leaders—it signals a historic evolution in how international law treats systemic gender oppression. For the first time, a government’s non-violent, bureaucratic repression of women—through education bans, mobility restrictions, and enforced erasure from public life—is being prosecuted under the banner of crimes against humanity.

While enforcement remains elusive, and Afghanistan's non-signatory status to the Rome Statute hampers immediate arrests, the legal precedent is powerful. It reframes how the world defines persecution, placing women's rights violations on the same level as other atrocities traditionally associated with war crimes.

What unfolds next may reshape the future of gender justice, especially if:

- Regional and global actors step in with sanctions or diplomatic isolation.

- Countries apply universal jurisdiction to restrict Taliban leaders' movement.

- International law bodies codify gender apartheid as a standalone crime.

If none of this happens, the ICC’s move risks becoming symbolic—another lofty gesture without teeth. But if the world acts on this legal landmark, it could rewire accountability structures not just in Afghanistan but in every nation where gender-based persecution still thrives under impunity.

A Final Question Worth Asking

Can this bold ICC action truly advance justice for Afghan women—or is it destined to be a symbolic strike that leaves systemic oppression untouched?

Let history and action be the judge!!

Sources

- ICC arrest warrant details and legal filings – ICC official documents:

https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/CourtRecords/0902ebd180a915c7.pdf - Amnesty International statement on ICC action against Taliban:

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/01/afghanistan-icc-prosecutors-application-for-arrest-warrants-against-taliban-leaders-is-an-important-step-towards-justice-for-afghan-women-girls-and-lgbtqi-persons/ - Legal analysis on gender persecution and ICC precedent – Atlantic Council:

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/taliban-persecution-of-women-crime-against-humanity/ - Ground reporting and quotes from Afghan women – The Guardian:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/23/icc-chief-prosecutor-seeks-arrest-warrants-for-taliban-leaders-over-persecution-of-women - Classroom photo of Afghan girls under Taliban rule – AP News (Associated Press):

https://apnews.com/article/afghanistan-taliban-schools-women-education-ban-3bacecb5e0b2f499c9b1674fd1bccc09 - Statistics and infographics on banned education – Human Rights Watch:

https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/03/24/one-year-taliban-still-attacking-girls-right-education - Visual reporting of Afghan girls protesting education bans – Al Jazeera English:

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/26/afghan-girls-protest-demanding-taliban-to-reopen-schools