South Korea’s Push to Revive the 2018 Inter-Korean Military Agreement: A Fragile Path to Peace?

South Korea's new government is pushing to restore the 2018 Inter-Korean Military Agreement to de-escalate tensions and reopen dialogue with North Korea. Discover what this renewed offer means for regional peace and security.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

SEOUL, August 15, 2025

South Korea’s new liberal President, Lee Jae-myung, has announced a landmark initiative to revive the 2018 Inter-Korean Military Agreement. This move, a stark reversal of the hardline stance of his predecessor, comes amid a period of heightened tensions and a prolonged diplomatic stalemate with North Korea. By seeking to re-establish a framework for military trust and de-escalation, Seoul hopes to prevent accidental skirmishes and lay the groundwork for a broader resumption of peace talks. However, the path is fraught with skepticism, particularly from a North Korea that has declared the South its "permanent enemy" and deepened its military alignment with Russia.

The Original Deal: Breaking Down the 2018 Inter-Korean Military Agreement

The 2018 CMA was a direct outcome of the historic diplomacy between South Korean President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Signed on September 19, 2018, in Pyongyang, the pact's primary objective was to reduce military tensions and prevent accidental clashes in a heavily fortified border region where a state of war technically still exists. The agreement was hailed as a significant confidence-building measure, going far beyond the 1953 armistice by introducing concrete, verifiable steps to reduce military provocations on land, at sea, and in the air.

Detailed Provisions and Their Goals

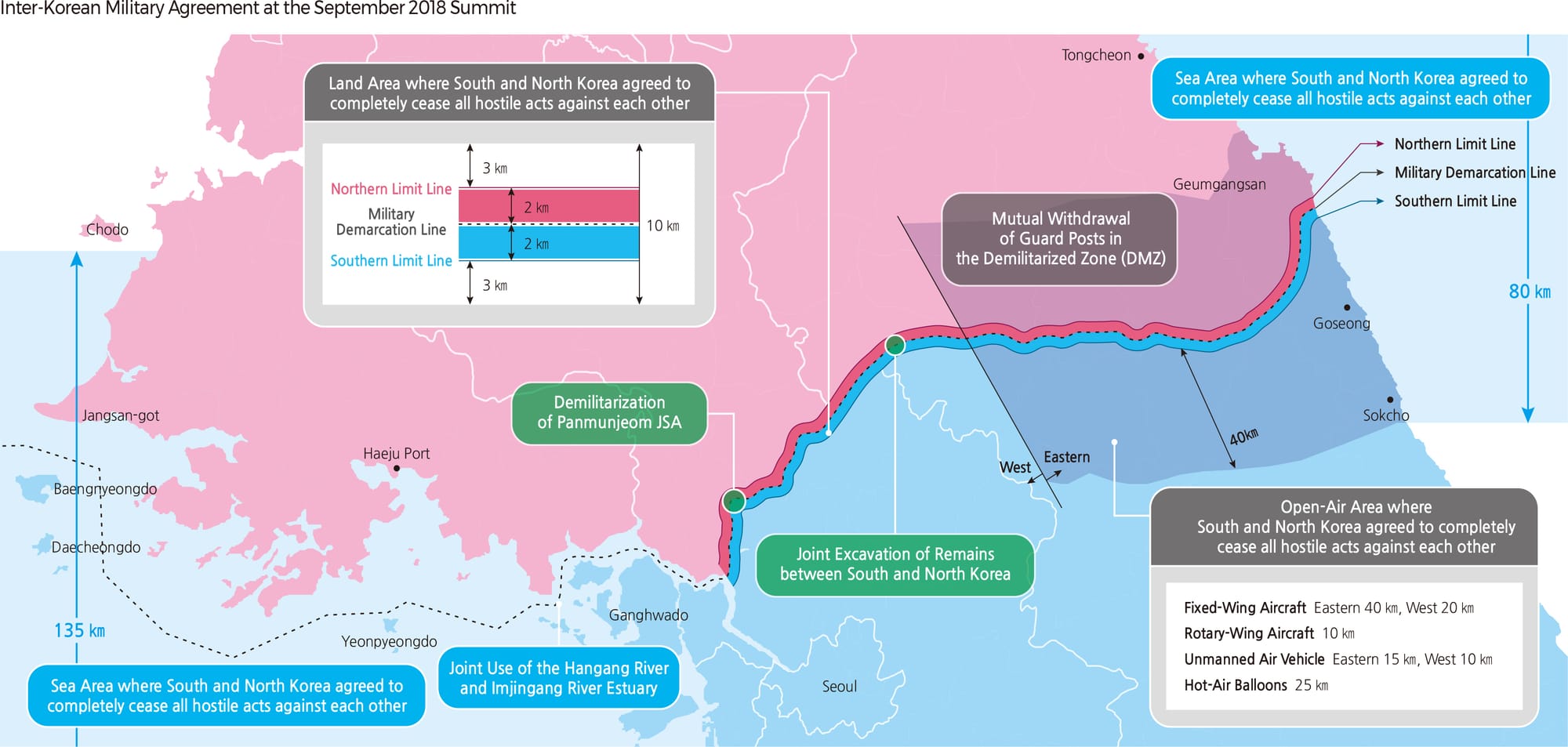

- Land-Based Buffer Zones and De-militarization: The agreement created a 5-kilometer buffer zone on each side of the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) where live-fire artillery drills and field training exercises were banned. This was a crucial measure to prevent miscalculations from escalating into a full-blown military exchange. It also called for the removal of all guard posts within the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), a symbolic and substantive step towards transforming the DMZ into a "peace zone." The most notable achievement was the disarmament of the Joint Security Area (JSA) in Panmunjom, where soldiers on both sides were to be replaced by unarmed civilian police guards.

- Maritime Peace Zone: In the West Sea, a sensitive area where several deadly clashes have occurred, the agreement established a "maritime peace zone." This provision banned all live-fire and maritime maneuver exercises within a designated area, aiming to prevent clashes over the disputed Northern Limit Line (NLL). It also included a provision for joint patrol teams to ensure safe fishing activities in the area.

- No-Fly Zones: To prevent accidental aerial confrontations, the CMA established no-fly zones along the border. These zones varied in depth, with fixed-wing aircraft banned from a 40-kilometer zone on each side of the MDL, helicopters from a 10-kilometer zone, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) from a 15-kilometer zone. This significantly restricted aerial surveillance capabilities, a move that was praised by some as a de-escalation measure but criticized by others as a potential security risk.

- Restoration of Communication: The agreement emphasized the importance of maintaining communication channels to prevent misunderstandings. It called for the establishment of a joint military committee to oversee implementation and a direct communication line to be used in case of emergencies.

The effectiveness of these measures was immediately apparent. For the period the pact was in effect, incidents of direct military confrontation along the border dropped to near zero, a testament to its practical function as a "last guardrail" against escalation.

The Collapse: A Timeline of Escalation and Reciprocity's Failure

The 2018 CMAs' success was inextricably linked to a favorable political climate, which quickly evaporated following the breakdown of the US-North Korea Hanoi Summit in 2019. The agreement's eventual collapse was not a single event but a gradual process of reciprocal military actions and diplomatic failures.

Timeline of Events Leading to the Collapse

- 2019-2022: Post-Hanoi Stalemate: Following the failure of denuclearization talks, North Korea began a series of missile tests, signaling its return to a policy of "byungjin" (parallel development of nuclear weapons and the economy). While the CMA technically remained in effect, North Korea's actions increasingly violated the spirit of the pact.

- November 2023: Satellite Launch: A critical turning point occurred in November 2023 when North Korea successfully launched its first military spy satellite, a clear violation of UN sanctions. In response, the then-conservative South Korean government, under President Yoon Suk-yeol, partially suspended the CMA's no-fly zone provisions, citing the need to resume aerial surveillance of the North.

- June 2024: Tit-for-Tat Escalation: North Korea's reaction was swift and predictable. Pyongyang formally declared that it would no longer be bound by the CMA and proceeded to restore the dismantled guard posts and redeploy heavy weaponry in the DMZ. In return, Seoul fully suspended the agreement, paving the way for the resumption of frontline propaganda loudspeaker broadcasts and military exercises. This cycle of escalation effectively nullified the pact and brought cross-border tensions to their highest point in years.

Seoul’s Renewed Offer: A New President, a New Strategy

President Lee Jae-myung's push to revive the CMA is a defining feature of his new administration's foreign policy. This strategy is rooted in the belief that de-escalation must precede any meaningful progress on denuclearization. The government's messaging, as articulated in President Lee's recent Liberation Day speech, has been one of outreach, respect, and a commitment to peaceful coexistence.

The Political and Diplomatic Implications:

- Reopening Dialogue: By offering to restore the CMA, Seoul is sending a clear signal that it is willing to meet North Korea halfway to rebuild trust. This move is a prerequisite for any future diplomatic engagement.

- Addressing the "Unification by Absorption" Fear: President Lee's government has been careful to affirm its "respect for the North's current system" and its lack of intent for "unification by absorption." This is a direct attempt to address a long-standing fear in Pyongyang and create a more conducive environment for talks.

- Potential Changes in Military Posture: Reviving the pact would entail an immediate reversal of the security measures put in place after its collapse. This would involve halting frontline propaganda broadcasts, re-implementing no-fly zones and buffer zones, and potentially re-disarming the JSA. This would affect surveillance, troop movement, and defense zones, creating a less volatile border environment.

This new diplomatic approach is an acknowledgment that the previous administration's hardline policies, while strong on deterrence, had failed to create any opportunity for dialogue, leading only to a dangerous cycle of provocation and retaliation.

The Geopolitical Chessboard: How Regional Powers Will Respond

The Korean Peninsula is a nexus of great power politics, and the fate of Seoul's initiative will not be decided by the two Koreas alone. The responses of the United States, China, Japan, and Russia will be critical.

- The United States: The US, as South Korea's primary security ally, will have a complex and multifaceted response. On one hand, the US supports stability on the peninsula and may view the CMA as a positive step towards de-escalation. On the other hand, the US is deeply invested in the denuclearization of North Korea and may be concerned that reviving the CMA could be seen as a concession without any progress on the nuclear front. The US-South Korea joint military exercises, which North Korea views as a direct threat, will remain a key point of contention.

- China: China, North Korea's most important economic and political partner, will likely support the revival of the CMA. A stable Korean Peninsula is in Beijing's interest, as a conflict would disrupt regional trade and create a humanitarian crisis on its border. China will use its influence to encourage dialogue, but its ultimate priority will be to maintain its strategic leverage over North Korea.

- Japan: Japan will be wary but open to the possibility of a successful peace process. The primary security concern for Tokyo is North Korea's ballistic missile program, which directly threatens Japan. Any measure that reduces tensions is welcome, but Japan will remain committed to its trilateral security cooperation with the US and South Korea to counter Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions.

- Russia: Russia's influence on the Korean Peninsula has grown significantly since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The deepening military cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang, which has seen North Korea supply Russia with ammunition and Russia provide technological assistance to the North, has fundamentally altered the geopolitical dynamics. Russia is likely to support the CMA as it serves its interests in reducing tensions with US-allied states, but it will also use its relationship with North Korea as a bargaining chip in its broader confrontation with the West. North Korea’s strategic importance has never been higher for Russia, making any diplomatic effort that doesn't account for this new reality likely to fail.

A Case History: The Long Road of Cooperation and Collapse

The current situation is best understood by examining the historical patterns of inter-Korean relations. The 2018 CMA was not an anomaly but a reflection of a recurring cycle of détente and tension.

- The Sunshine Policy (1998-2008): This policy, initiated by President Kim Dae-jung, was the first concerted effort to engage North Korea through dialogue and economic cooperation. It led to the first-ever inter-Korean summit in 2000, family reunions, and the establishment of the Kaesong Industrial Complex. While it did not resolve the nuclear issue, it demonstrated the potential of a peaceful approach.

- The 2007 Inter-Korean Summit: A second summit was held in 2007 under President Roh Moo-hyun, leading to a joint declaration on peace and economic cooperation. These efforts, however, were short-lived, as a change in leadership in both Koreas and North Korea's continued nuclear program led to a return to a more confrontational stance.

- The 2018 Summits: The three summits in 2018, culminating in the Panmunjom Declaration and the CMA, represented the most significant progress since the end of the Korean War. They sparked international optimism but were ultimately dependent on a fragile foundation of trust that crumbled as the broader international context shifted.

An Analysis of Pyongyang’s Possible Reactions

North Korea’s response is the key unknown in this equation. The past year has seen Pyongyang repeatedly rebuff South Korean overtures, with Kim Jong-un’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, publicly mocking Seoul’s "pipedream" of dialogue.

- Outright Rejection: The most likely scenario is that North Korea will either ignore the offer or formally reject it. Pyongyang's strategic priority is to be recognized as a nuclear power, and it sees little to gain from a peace deal with Seoul that does not lead to a lifting of international sanctions.

- Leverage for Concessions: A less probable, but still possible, outcome is that Pyongyang might use the offer to extract concessions. North Korea could demand an end to all US-South Korea military exercises or a unilateral lifting of sanctions by Seoul.

- Military Provocations: North Korea may respond with new military provocations, such as ballistic missile tests, to demonstrate its strength and its contempt for a deal it has already unilaterally abandoned. This would be a clear message that it is not interested in diplomacy on Seoul's terms.

The Economic and Social Impact of Peace Agreements

The pursuit of peace has profound effects on the economies and societies of both Koreas.

- Trade and Investment: Periods of détente have historically led to an increase in inter-Korean trade and investment, most notably the Kaesong Industrial Complex. A lasting peace agreement could unlock significant economic potential, benefiting South Korean companies and providing much-needed capital and resources for North Korea.

- Security Budgets: The perpetual state of tension on the Korean Peninsula has led to massive defense spending by both countries. South Korea, for example, consistently ranks among the top global defense spenders, with its military budget exceeding $50 billion annually. A successful peace process could lead to a reallocation of these funds to social and economic programs, a key objective for a liberal government.

- Public and National Psyche: For the South Korean public, a peace agreement would be a profound psychological shift. It would move the nation from a state of constant readiness for war to one of hope for a future of stability and eventual reunification. Conversely, a failed peace effort reinforces public cynicism and the belief that lasting peace with the North is an unattainable goal.

The Grand Experiment

South Korea's push to revive the 2018 Inter-Korean Military Agreement is a bold and necessary gamble for peace. It represents a fundamental shift away from the brinkmanship of the past and a return to a strategy of engagement and trust-building. While North Korea's recent dismissive reactions and its deepening ties with Russia make the prospects for success appear slim, the alternative, a continued cycle of provocation and escalation, is far more dangerous. The world's most heavily armed border, where a single miscalculation could ignite a catastrophic conflict, cannot be left to a policy of neglect.

The CMA, even in its limited capacity, proved to be an effective tool for preventing accidental skirmishes. Its restoration would not solve the core issue of denuclearization, but it would provide a much-needed foundation of stability. It is a vital first step, a small but significant gesture that signals a willingness to listen and engage. For this effort to succeed, it will require not only patience and perseverance from Seoul but also a new level of diplomatic imagination from its international partners.

Can Diplomacy Outlast Provocation?

This new approach is a real-world experiment to see if the patient, the persistent diplomacy of a liberal government, can withstand the aggressive, isolationist policies of a nuclear-armed state. Can trust be rebuilt in the absence of a shared vision for the future?

Sources

The Associated Press, The Korea Times, The Independent, and The Institute for Security & Development Policy.