The Global Hunger Paradox: Why the World Is Improving and Starving at the Same Time

Explore the unsettling paradox of global hunger. Discover how SOFI 2025 data reveals declining hunger overall, yet a worsening crisis in Africa and Western Asia. Uncover the drivers - war, climate change, and food costs, and the innovative solutions fighting back.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

Rome, August 7, 2025

The world is living through a profound and unsettling paradox. Despite unprecedented global progress in technology and food production, a staggering number of people are still going hungry. While headlines celebrate a steady decline in global hunger rates, a deeper dive into the data reveals a far more complex and troubling reality: in some parts of the world, hunger is not just persistent—it is actively worsening. This dual reality, as outlined in the landmark State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2025 report, demands our immediate attention. It’s a story of progress and catastrophe, of innovation and inaction, and of a world becoming simultaneously more connected and more unequal.

This investigative report dissects the SOFI 2025 findings, exploring why hunger is declining in some regions while spiraling out of control in others. We will analyze the potent forces driving this divergence—from modern warfare and climate change to rising food costs and systemic inequalities—and examine both the proven solutions and the urgent questions that remain.

A Tale of Two Worlds: The Global Divergence

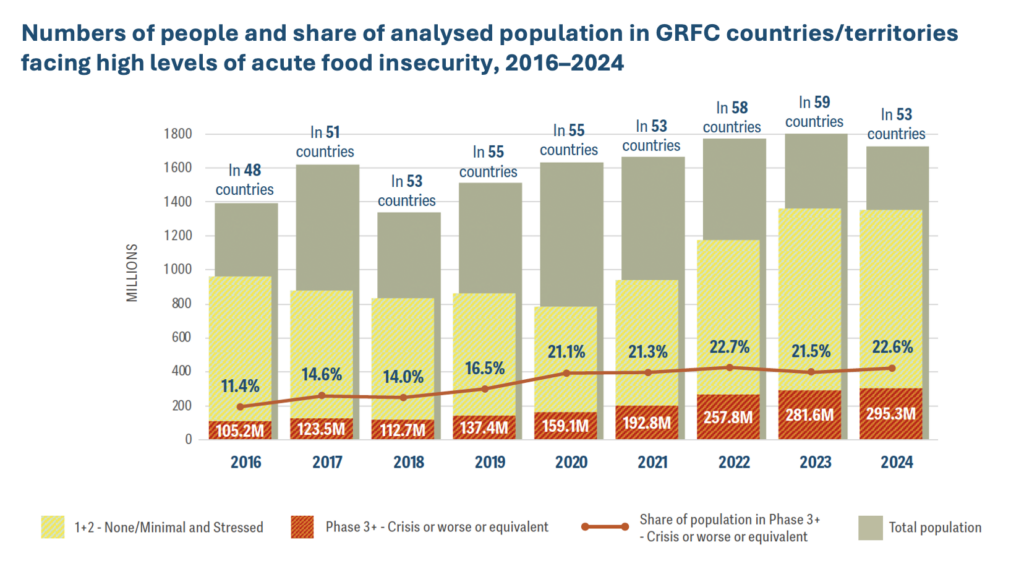

The SOFI 2025 report offers a fragile piece of good news: the number of people experiencing hunger globally fell to 673 million in 2024, a modest drop from 8.5% of the population in 2023 to 8.2%. This progress is largely a testament to concerted efforts and economic recovery in Southern Asia and Latin America, where the prevalence of undernourishment has seen a notable decline. However, this is where the good news ends and the paradox begins.

In stark contrast, hunger is on a dramatic and concerning rise in Africa and Western Asia. The report reveals that over 307 million people in Africa, more than one in five, faced chronic hunger in 2024. In Western Asia, the number surpassed 39 million people, a 12.7% prevalence rate that marks a steady increase largely ignored by global conversations. This divergence is not an accident of geography; it is a direct consequence of a food system deeply fractured by instability and inequality.

The New Trinity of Hunger: War, Climate, and Cost

The SOFI 2025 report identifies a perfect storm of factors driving this new era of hunger, a destructive trinity of modern challenges that are eroding food security from the top down.

Modern Warfare: The Weaponization of Hunger

Historically, war and famine have been grim companions. Today, warfare is strategically targeting the very systems that feed people. The war in Ukraine, a global breadbasket, caused a massive disruption in the supply of wheat, maize, and fertilizer. This shockwave sent global food prices soaring, making basic nutrition unaffordable for millions in low-income countries already struggling.

In Sudan, a brutal civil war has triggered one of the world's most catastrophic hunger crises. Fighting has decimated agricultural infrastructure, displaced over 12 million people, and created an environment where famine is not just a threat, but a reality. An IRC country director for Sudan noted, "This crisis is entirely man-made. The ongoing conflict has decimated livelihoods, displaced millions, and blocked life-saving aid from reaching those in desperate need." In Gaza, the situation is even more dire. A siege and intense conflict have systematically destroyed greenhouses, livestock, and bakeries, leaving a significant portion of the population facing "catastrophic levels of food insecurity" and, in some cases, famine conditions.

Climate Change: The Unpredictable Adversary

The climate crisis is a powerful accelerant of hunger, particularly in Africa. A World Bank analysis found that climate-induced extreme weather events like droughts and floods are becoming more frequent and intense, directly threatening agricultural productivity. For example, severe droughts in the Horn of Africa have decimated livestock and crop yields, pushing millions into food insecurity. At the same time, unpredictable rainfall and rising temperatures are making traditional farming practices obsolete, forcing smallholder farmers to abandon their land and migrate to already overcrowded cities.

Rising Food Costs: The Affordability Crisis

Since 2020, global food price inflation has consistently outpaced general inflation, hitting low-income countries the hardest. The SOFI 2025 report highlights that this trend has made a healthy diet unaffordable for over 2.6 billion people. For many, this means a daily choice between skipping meals, selling assets, or pulling children out of school. The rise in food costs isn't just about a lack of calories; it's about the inability to afford nutritious food, which leads to a more insidious problem: "hidden hunger."

The Silent Epidemic: Hidden Hunger and Its Consequences

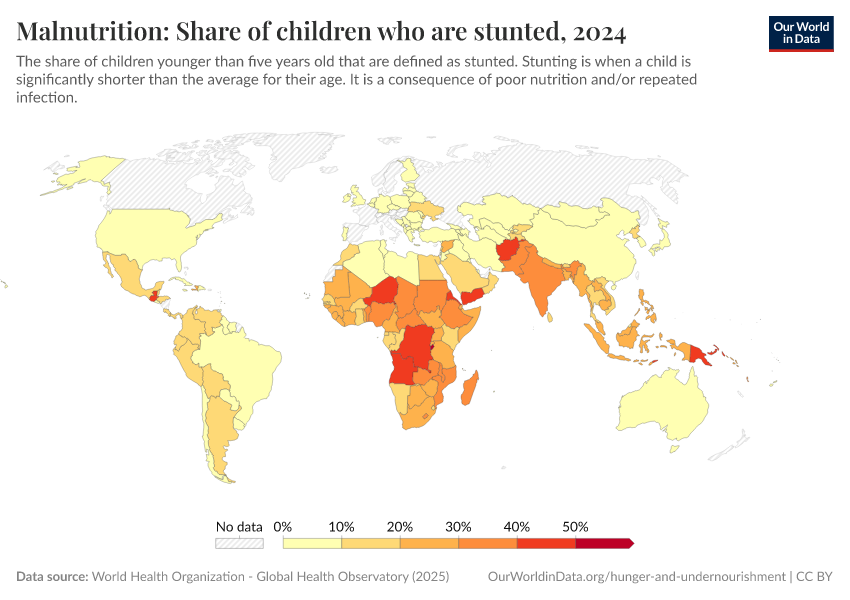

Even in regions where caloric intake may seem sufficient, a different form of malnutrition is silently undermining human potential. Hidden hunger is the deficiency of essential micronutrients like iron, zinc, and Vitamin A. It's a critical paradox: people are eating, but they are not getting the right nutrients. The SOFI 2025 report reveals that while global stunting rates in children under five have declined to 23.2% in 2024, this progress is far too slow.

Hidden hunger has devastating, long-term consequences. It leads to childhood stunting, which causes irreversible damage to a child's cognitive development, educational performance, and future earning potential. A study cited in the report estimates that the economic costs of undernutrition, in terms of lost national productivity and growth, can reach up to 11% of GDP in some African and Asian countries. This is a powerful indictment of a global food system that prioritizes cheap calories over comprehensive nutrition.

The Rise of Urban Hunger

As the global population becomes increasingly urban, particularly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, a new front in the fight against hunger has emerged: urban hunger. People migrating from rural areas often face precarious, low-paying jobs that are highly vulnerable to economic shocks. Unlike their rural counterparts, they lack the ability to produce their own food, making them completely dependent on market prices. This has created a new class of urban poor for whom a food price shock can mean instant starvation. The SOFI 2025 report notes that the number of people in urban areas experiencing food insecurity is growing at an alarming rate, a challenge that traditional humanitarian and development models are ill-equipped to handle.

Tackling the Paradox: Innovation and a New Approach

Despite the complex challenges, there are glimmers of hope and proven strategies that offer a way forward.

Sustainable and Climate-Friendly Farming

The long-term solution to hunger and environmental degradation is to transform our food systems. Agroecology and regenerative agriculture are two key pathways. These practices build healthy soil, increase biodiversity, and make farms more resilient to climate shocks. By mimicking natural ecosystems, they can enhance food production while reversing environmental damage. For example, a project in Ethiopia has shown that smallholder farmers using agroecological methods were able to increase their yields by up to 20% while simultaneously improving soil fertility.

Technology and Data: The Future of Food

Technology is a powerful tool in the fight against hunger. Precision agriculture uses AI, satellite imagery, and IoT sensors to help farmers apply water, fertilizer, and pesticides more efficiently, increasing yields and reducing waste. Furthermore, blockchain and big data analytics are enhancing food supply chain transparency, ensuring food safety and reducing waste. These technologies are not just for large-scale farms; they are increasingly being adapted for use by smallholder farmers, giving them the data they need to make informed decisions and improve their livelihoods.

Reimagining Foreign Aid

The debate over foreign aid has been long-standing, but a new consensus is emerging. While short-term food aid is crucial in a crisis, long-term solutions require investment in a country's own food systems. The most effective aid programs are those that empower local communities, support women farmers with access to land and credit, and fund agricultural research and development. An IFPRI study suggests that for every dollar invested in agricultural research, countries can see up to nine dollars in return, a powerful argument for a new kind of aid that builds capacity, not dependence.

What Happens Next? A Call to Action

The Global Hunger Paradox is not an unsolvable mystery. It is a man-made crisis that can be addressed with a concerted, multifaceted approach. It requires us to move beyond simple calorie counts and address the root causes of food insecurity: conflict, climate change, and inequality.

We must:

- Integrate humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding efforts: In conflict zones, food aid must be combined with long-term initiatives that rebuild agricultural infrastructure and promote social cohesion.

- Invest in climate-resilient agriculture: Governments and international organizations must prioritize funding for sustainable farming practices that can withstand climate shocks.

- Empower women: Given that women are often the primary food producers and caretakers in many communities, policies must be designed to grant them equal access to land, education, and financial resources.

- Address urban hunger: We must develop new strategies and social safety nets specifically tailored to the unique challenges faced by the urban poor.

- Hold our leaders accountable: Citizens, journalists, and policymakers must demand that our global food systems are not just productive, but also equitable, sustainable, and resilient.

This is a pivotal moment. The choice is clear: we can either continue to treat hunger with a patchwork of reactive solutions, or we can embrace a new, holistic approach that addresses the systemic flaws in our world and ensures that no one is left behind.

The Hunger Divergence Theory

The data from the SOFI 2025 report suggests a new theoretical framework: The Hunger Divergence Theory. This theory posits that in an increasingly globalized world, while the total volume of food production and distribution increases, the stability and equity of access decrease. Globalized trade and supply chains can buffer some regions from localized shocks, but they also create a domino effect when a major disruption occurs (e.g., the war in Ukraine). This leads to a divergence: countries with stable economies, strong governance, and resilient food systems see a decline in hunger, while those in conflict, with fragile governance, or heavily exposed to climate change, see a catastrophic increase. The paradox is not an anomaly; it is the predictable outcome of a global system that is unequal by design.

Time to ponder

How can technology and data be made accessible and affordable for the millions of smallholder farmers who need it most? How can we shift the focus of foreign aid from short-term relief to long-term systemic change without creating new forms of dependency?

Sources

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2025 Report.

- World Food Programme (WFP).

- International Rescue Committee (IRC).

- World Health Organization - Global Health Observatory (2025).

- The World Bank.

- Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC) 2024.

- International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

- Verified public footage and official press releases from global NGOs.