The State-backed Chip Gambit: Is America Building a New Semiconductor Monopoly?

The United States' audacious shift from subsidizing to directly investing in semiconductor giants like Intel, TSMC, and Samsung signals a dramatic escalation in the global chip war.

Written by Lavanya, Intern, Allegedly The News

Los Angeles, California, August 20, 2025

A Timeline of Escalation: From Subsidies to Stakes

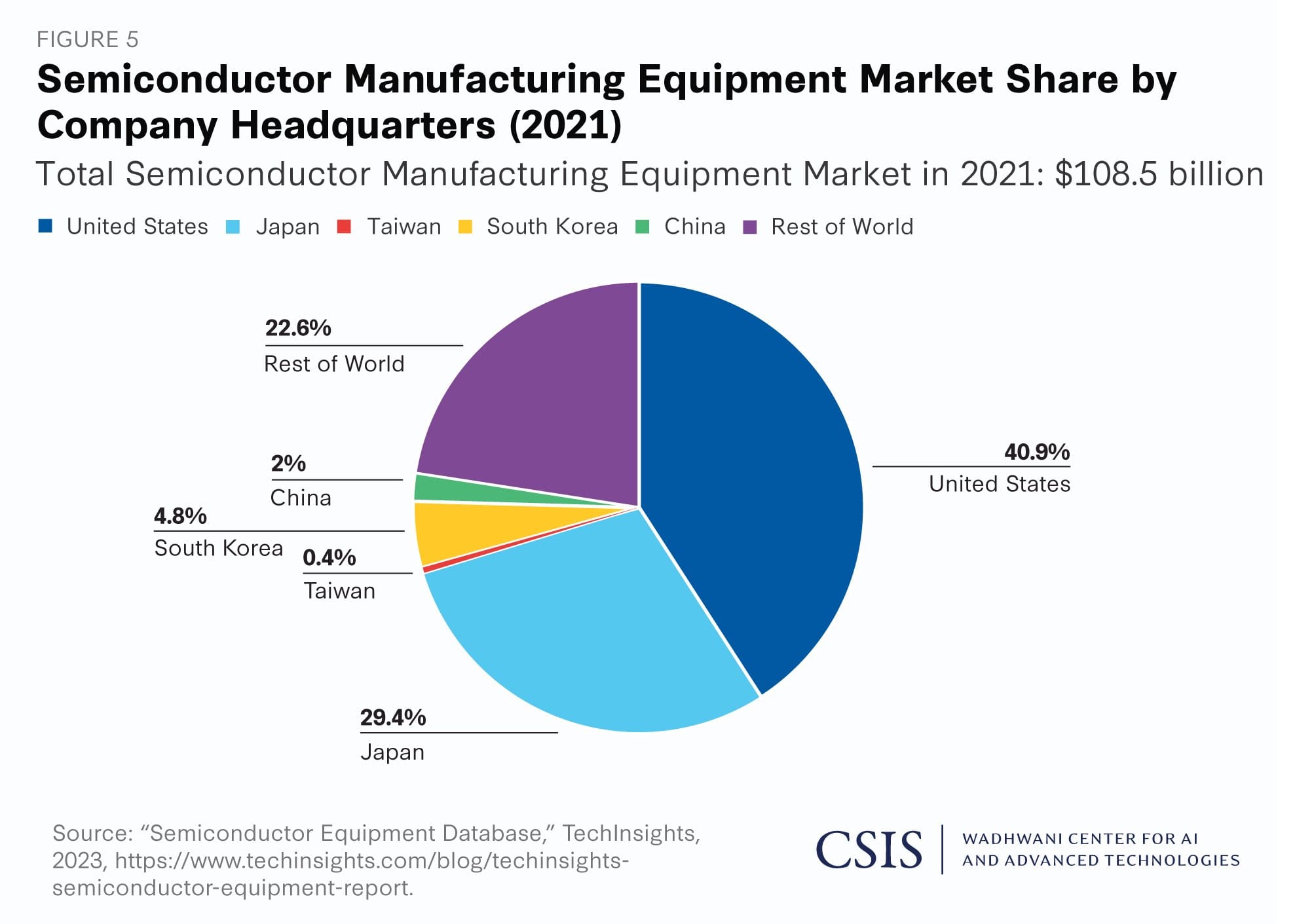

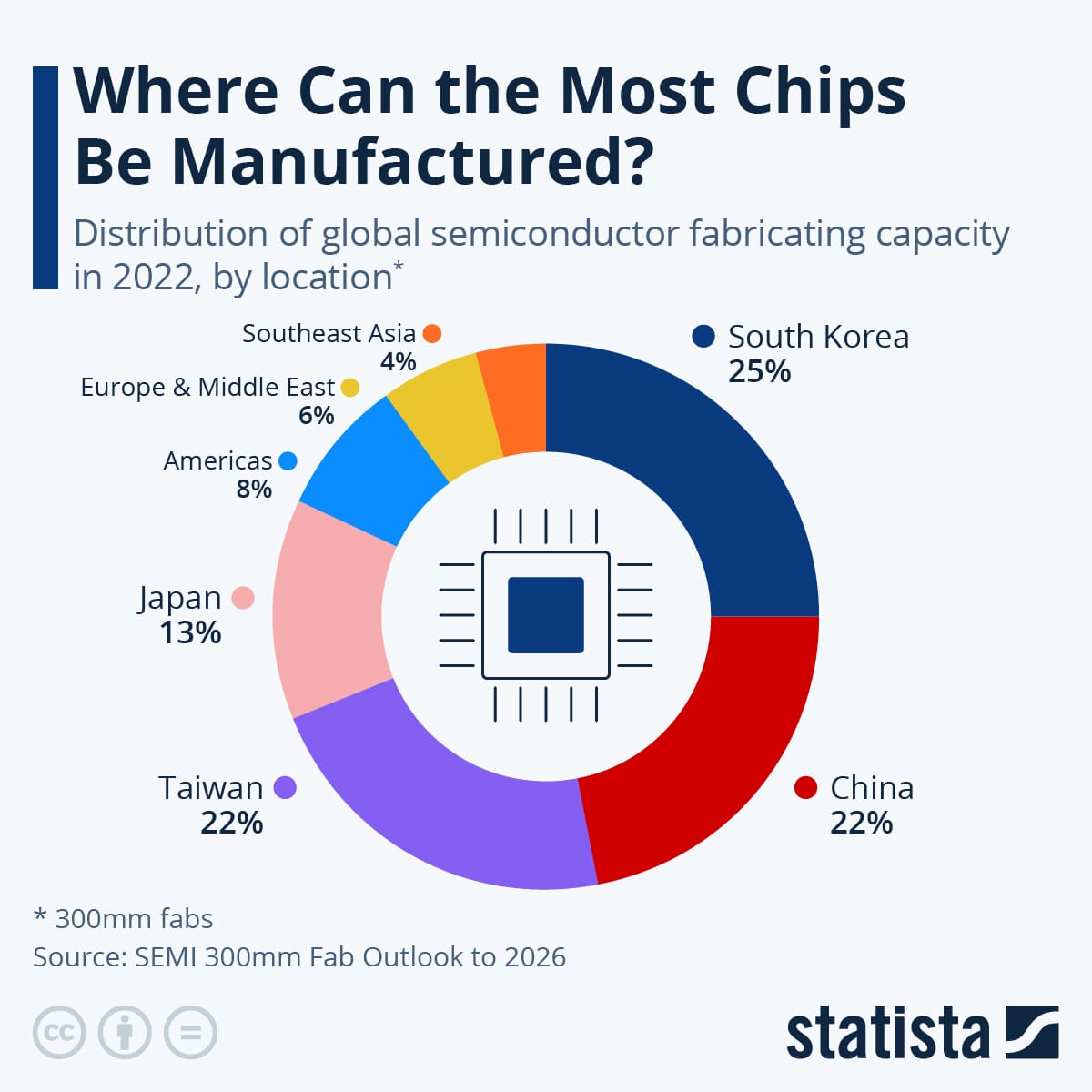

The U.S. government's recent pivot isn't a sudden whim; it's the latest, most dramatic chapter in a long-running saga of industrial policy, supply chain anxiety, and geopolitical rivalry. For decades, the American semiconductor industry, while dominant in design, had outsourced the complex and expensive manufacturing process to Asia. This outsourcing created a single point of failure and a national security risk, as highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic-induced chip shortages. This timeline traces the U.S. response from a foundational legislative effort to a potential, unprecedented shift in economic strategy.

- August 2022: The CHIPS and Science Act is Born. In a bipartisan effort to reassert American leadership in semiconductor manufacturing, President Joe Biden signed the CHIPS and Science Act into law. The act authorized roughly $280 billion in new funding, with $52.7 billion specifically appropriated for semiconductor research and manufacturing subsidies. The core philosophy was simple: use a mix of grants, loans, and tax credits to incentivize private companies to build and expand domestic fabrication plants, or "fabs." The relationship was a partnership, not an ownership stake. Companies like Intel, TSMC, and Samsung were slated to be the largest beneficiaries.

- 2023-2024: The Grant Distribution Begins. The Department of Commerce began the painstaking process of distributing the CHIPS Act funds. Intel was awarded a massive $8.5 billion in grants and $11 billion in loans to support its U.S. fab projects in Arizona, Ohio, and New Mexico. TSMC, a primary target for reshoring, secured $6.6 billion for its three-fab complex in Phoenix, Arizona. Samsung was granted $6.4 billion for its multi-fab investment in Taylor, Texas. These awards came with strict "guardrails" designed to prevent recipients from using the money to expand in countries of concern, primarily China. This was the initial phase of the American semiconductor comeback, focused on building physical infrastructure.

- August 2025: Intel Talks Spark a New Model. A groundbreaking report from Bloomberg revealed a new, more aggressive plan being weighed by the Trump administration. Following a meeting between President Trump and Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan, a proposal was reportedly put forward to convert a portion of Intel's CHIPS Act grants, potentially up to $10.5 billion of the total, into a roughly 10% equity stake in the company. This radical idea, championed by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, represented a fundamental shift from the CHIPS Act's original intent. Instead of just subsidizing private enterprise, the U.S. government would become an active shareholder, with the stated goal of giving the American taxpayer a "piece of the action."

- Today: The Global Gambit. Following the Intel discussions, sources close to the administration have confirmed that Washington is now exploring similar equity-stake deals with other key CHIPS Act recipients, including Micron, Samsung, and TSMC. This signals a broad, systemic shift in U.S. industrial policy, moving from a facilitator role to an active, state-backed shareholder. The rationale is to secure influence over a crucial sector deemed a matter of national security, not just economic competitiveness.

The Anatomy of the Deal: Why Washington is Eyeing the Big Three

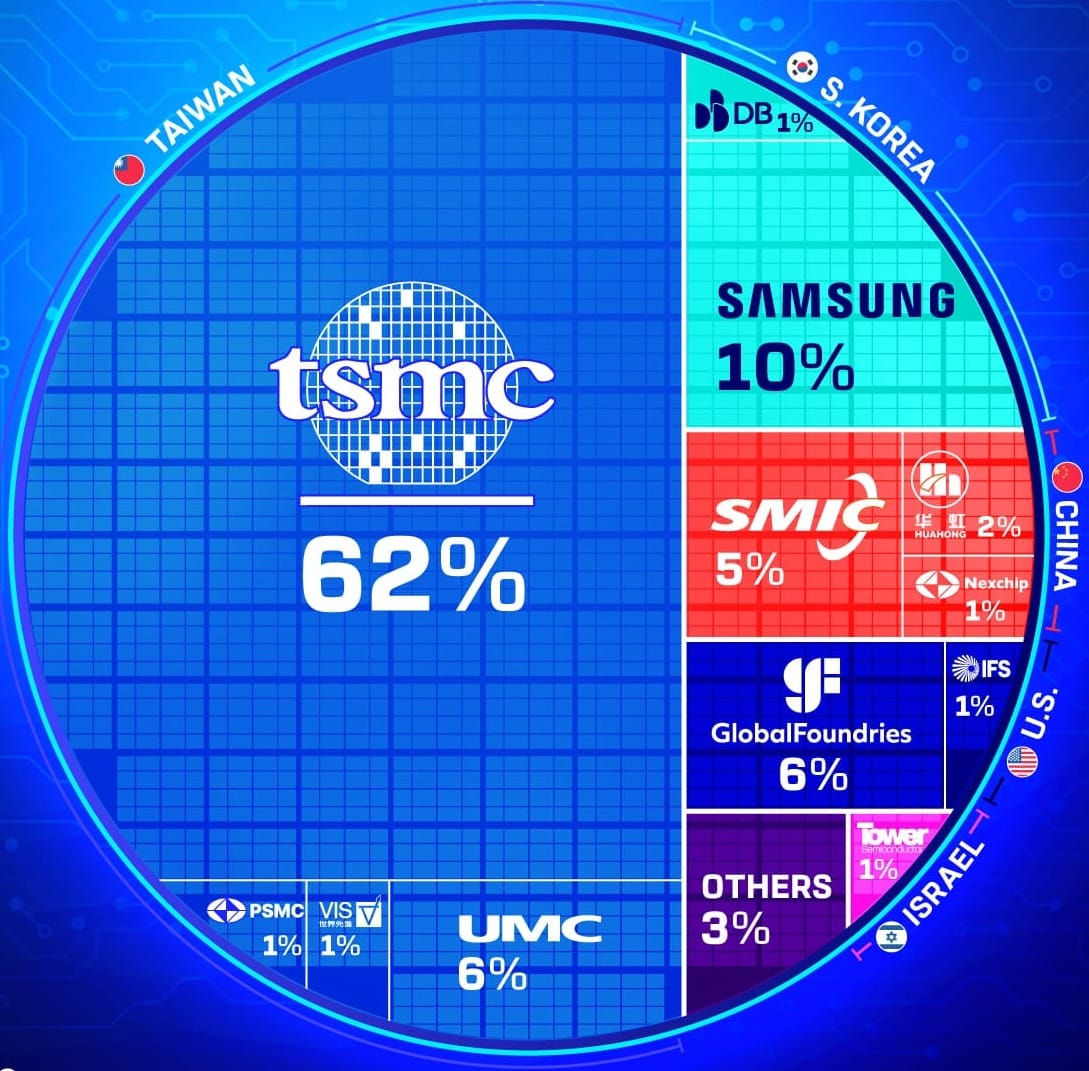

The U.S. isn't just looking to shore up Intel; the strategic rationale for targeting Micron, Samsung, and TSMC is a multi-faceted approach to securing different parts of the semiconductor supply chain. This is a targeted effort to gain influence over memory chips, foundry services, and cutting-edge fabrication—the three pillars of modern chip dominance.

Micron Technology (MU): The Memory King

Micron is a global leader in memory and storage solutions, a critical and often overlooked part of the semiconductor ecosystem. These chips are essential for everything from data centers and AI models to smartphones and military hardware. U.S. control over Micron would provide a strategic advantage in a high-demand, high-volume segment, reducing reliance on South Korean and Chinese competitors. The company has already committed to investing $200 billion in domestic manufacturing and R&D in Idaho and New York, but a government stake could provide a permanent anchor, ensuring these crucial assets never fall into foreign hands or are diverted from national interests.

Samsung Electronics (SSNLF): The Foundational Force

Samsung is a multifaceted giant with a major foundry business that competes directly with TSMC. Its $4.75 billion CHIPS Act grant and $17 billion investment in a new fab in Taylor, Texas, are a cornerstone of the U.S. reshoring strategy. By taking a stake in Samsung, the U.S. would gain a foothold in one of the world's largest chipmakers, influencing its strategic direction and ensuring a stable, high-tech foundry presence in the U.S. This is about more than just manufacturing capacity; it’s about controlling the underlying technology and intellectual property that powers devices around the world.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC): The Crown Jewel

TSMC is the undeniable king of the semiconductor world, a near-monopolist in the production of advanced, cutting-edge chips. Its dominance is a source of both admiration and geopolitical anxiety. Its $6.6 billion CHIPS Act grant is tied to a staggering $65 billion investment in three fabs in Arizona, a move explicitly designed to mitigate the national security risk posed by its location near a potential conflict zone. A U.S. equity stake in TSMC would be the most audacious move of all. It would grant Washington unprecedented influence over the fabrication of the world's most critical chips, effectively bringing the heart of the global supply chain under American sway. Such a deal would be highly symbolic, sending a clear message to both allies and adversaries that the U.S. intends to be in control of its technological destiny.

Financial and Strategic Implications: The Chip War on the Balance Sheet

The potential for U.S. ownership stakes in these companies presents a complex web of financial and strategic implications. The benefits are clear, but so are the risks.

For the Companies:

- Financial Lifeline: For companies like Intel, which has struggled with repeated delays and yield issues on its next-generation 18A process, a government stake could serve as a much-needed capital injection and a vote of confidence, stabilizing its stock and providing cash for R&D and fab construction. The recent $2 billion investment from SoftBank—which made SoftBank the fifth-largest shareholder—followed initial reports of the government's interest, suggesting that federal backing can attract private capital.

- Strategic Alignment: The trade-off for this capital is a loss of complete autonomy. While the proposed stakes are "non-voting," a government shareholder—especially one tied to future subsidies—will exert significant influence. This could mean a shift in corporate priorities to align with national security interests, even if it means sacrificing short-term profitability.

For the U.S. Government:

- Return on Investment: Unlike the CHIPS Act's "free money" grants, an equity stake allows the government to profit if the companies succeed. This is a politically appealing narrative, framed as a responsible use of taxpayer funds. President Trump has reportedly championed this approach with the slogan, "We want a piece of the action for the American taxpayer."

- Enhanced Influence: A seat at the table, even a non-voting one, gives Washington unparalleled access to internal strategy discussions and a powerful tool to shape decisions. This influence extends beyond just where fabs are built; it can affect everything from R&D roadmaps to supply chain partners.

CHIPS Act vs. Equity Stakes: The Great Policy Pivot

This new approach is fundamentally different from the CHIPS Act. The CHIPS Act was a carrot-and-stick model: provide incentives to companies that agree to build in the U.S. The relationship was transactional. The equity stake model, however, is a marriage. It creates a direct, long-term entanglement between the U.S. government and the world's most critical chipmakers.

This is an escalation driven by a number of factors:

- Growing Distrust: There's a rising belief in Washington that grants alone aren't enough to secure long-term semiconductor independence. Past policies have often failed to prevent tech from leaking to rivals.

- The Chinese Threat: The U.S.-China tech rivalry has intensified. Semiconductors have become the frontline of this tech war. China's domestic efforts, despite U.S. export controls, have advanced rapidly. Washington is seeking a more permanent and direct mechanism to ensure its lead.

- A "Golden Share" Model: The equity stake model mirrors a "golden share" approach, where a government retains a small, often non-voting, stake in a privatized or strategically important company to block hostile takeovers or ensure national interests are protected. The U.S. has used a similar approach in the past, for example, by securing a "golden share" in US Steel after approving its sale to Japan’s Nippon Steel.

Innovation and Monopoly: The Double-Edged Sword

One of the most significant debates surrounding this strategy is its impact on innovation. The question is whether government influence will accelerate or hinder technological progress.

Accelerated Innovation:

- Consolidated Research: With government backing and potential coordination, research and development efforts could be streamlined, preventing redundant work and focusing resources on critical, next-generation technologies. The National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Program (NAPMP), for instance, aims to accelerate domestic R&D in a crucial area of chipmaking, and a government stake could fast-track such initiatives.

- De-risked Investment: Government stakes could act as a safety net, encouraging companies to take on riskier, long-term R&D projects that they might otherwise avoid due to market pressures.

Hurdled Innovation:

- Market Distortion: Government intervention can distort a free market. If companies are guided by strategic directives rather than pure market demand, it could hinder organic innovation and discourage smaller, more agile competitors.

- Bureaucratic Drag: Direct government influence could introduce bureaucratic hurdles and slow down decision-making, a fatal flaw in the fast-paced semiconductor industry. As tech analyst Gil Luria has noted, without a "solid process roadmap," a U.S. investment in Intel would be economically equivalent to simply setting 10s of billions of dollars on fire."

The Global Fallout: Trade, Supply Chains, and Diplomacy

This new strategy isn't just a domestic policy shift; it has the potential to trigger a cascade of international consequences. The ripple effects will be felt across trade, supply chains, and diplomacy, with both allies and adversaries watching closely.

- Diplomatic Tensions: The idea of a U.S. stake in TSMC or Samsung is likely to be met with diplomatic resistance from Taiwan and South Korea, who see these companies as symbols of their national pride and economic sovereignty. It could be perceived as a form of economic imperialism, as the U.S. attempts to exert control over the crown jewels of its national economies.

- Supply Chain Disruption: If the U.S. pushes its newfound influence to redirect supply chains and force companies to prioritize American customers, it could create new bottlenecks and instability for allied nations that rely on these chips. This could lead to a fragmentation of the global supply chain, with countries building their own walled-off ecosystems.

- The China Factor: China, already locked in a tech war with the U.S., will see this move as a direct escalation. It could accelerate its own efforts to achieve semiconductor self-sufficiency and retaliate with its own forms of trade restrictions or investment policies, further entrenching the tech rivalry.

Who Wins and Who Loses? A Power Shift Analysis

The outcome of this bold strategy will create clear winners and losers across the globe.

Winners:

- U.S. Domestic Chipmakers: Companies like Intel, which are the primary focus of this new policy, stand to benefit most from both financial infusions and a protected, state-backed market.

- The U.S. Military & Tech Industry: The primary goal is national security. The U.S. government and its contractors will benefit from a more secure and predictable supply of advanced chips, which are critical for defense and AI superiority.

- Investors: For a time, investors may see a bump in stock prices for companies that are being propped up by government funds, as seen with the recent surge in Intel's stock following news of the potential government investment.

Losers:

- Foreign Competitors: European, Japanese, and other Asian semiconductor companies that are not part of the U.S. inner circle may find themselves at a disadvantage, squeezed out of key markets and access to U.S. technology.

- The Global Free Market: The shift from a market-driven industry to a state-controlled one could undermine the principles of free trade and open competition, leading to a less efficient and innovative global system.

- Consumers: Supply chain fragmentation and a less competitive market could eventually lead to higher prices for everything from smartphones to cars, as the cost of doing business in a bifurcated world is passed down.

The New Industrial Revolution and the Return of the Trust

The U.S. government's move is not merely a policy change; it's a theoretical shift. The traditional American model of laissez-faire capitalism, with government acting as a hands-off regulator, is being replaced by a new form of state capitalism. Washington is no longer just subsidizing; it's directly investing, becoming a partner, and in some cases, a partial owner. This return to an industrial policy reminiscent of the post-WWII era or even the monopolistic "trusts" of the Gilded Age, but this time with the government as the trust-holder, suggests a profound and perhaps irreversible transformation. The pursuit of national security and technological dominance has become so paramount that the U.S. is willing to abandon its own economic orthodoxy to secure a strategic lead, potentially at the cost of the very globalized, open-market system it helped create.

Navigating a New Reality: The Open Questions

This new era of government intervention raises profound questions that will shape the future of technology and geopolitics.

- Is a non-voting equity stake truly "non-voting"? Can the government, as a major shareholder, resist the urge to influence corporate decisions, or is this a form of de facto control that could be detrimental to the private sector and market-driven innovation?

- How will this strategy impact the global supply chain? Will it create a resilient, diversified network, or a fragmented, inefficient one? What steps might other countries, including key allies, take in response to what could be perceived as American overreach?

Sources

Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journal, Reuters, Al Jazeera, CSIS, and various companies and government press releases.