When Homicides Kill Growth: The Hidden Cost of Crime in Latin America

In Latin America, rising homicide rates aren’t just a public safety crisis they’re an economic one. From deterring investors to driving talent away, crime quietly drains billions from the region’s potential for sustainable growth.

Latin America carries a paradox: a region rich in natural resources, human capital, and entrepreneurial energy, yet continually held back by violence. Homicides aren’t only tragedies for families and communities they are a structural drain on economies. This deep dive explores how homicides reduce growth, where the costs show up, why the region remains vulnerable, and what a realistic path out of the cycle might look like.

A blunt arithmetic: violence eats growth

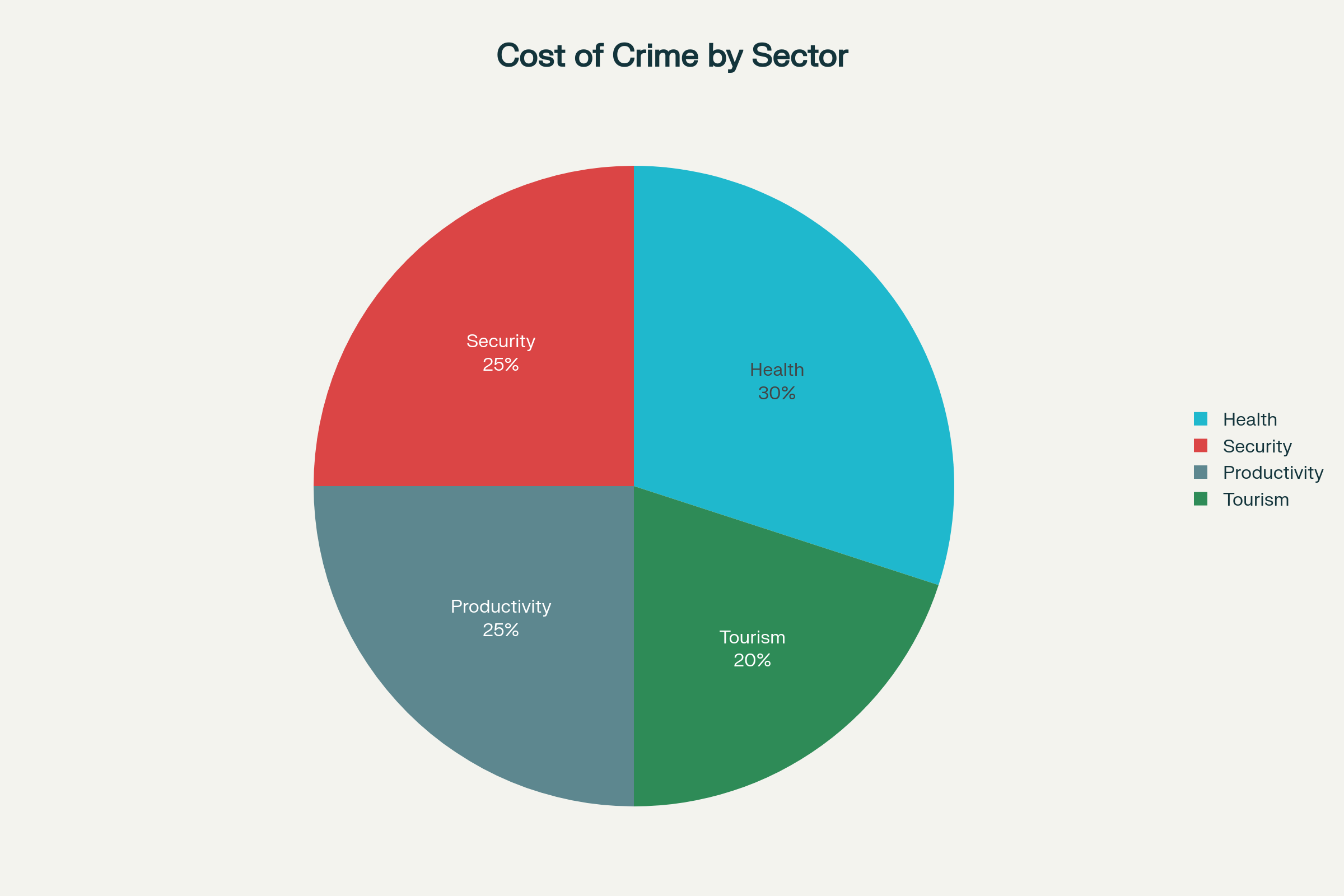

Recent regional studies estimate that crime and violence cost Latin America roughly 3.4–3.5% of regional GDP each year an amount that rivals or exceeds many countries’ education budgets and social spending. Those costs are not hypothetical: they add up across productivity losses, private security spending, public spending on policing and prisons, lower investment, and lives cut short at prime working ages. In short, homicide is not a marginal problem; it is an economic headwind. Inter-American Development Bankpublications.iadb.org

The relationship is causal as well as correlative. Analysis by international financial institutions shows that rises in homicide reduce GDP growth measurably even modest increases in violence translate into lower short-run growth rates, and the cumulative effects compound over time. In other words, safety is not only a social good; it’s an economic policy lever. IMF

How homicide translates into lost output the channels

To understand the scale of the problem, it helps to unpack the primary channels by which lethal violence damages economies:

- Human capital and productivity loss. Homicides disproportionately affect young men — the region’s working-age cohorts. Each premature death removes productive labor and robs households of income and future consumption. Widespread violence also discourages school attendance and reduces lifetime learning. The net effect is lower productivity across the population.

- Private security and business costs. Firms respond to insecurity by spending more on guards, armored transport, alarms, and insurance premiums. These are deadweight losses: money that could otherwise go into hiring, innovation, or investment. In some countries private security expenditure is a very large share of total crime costs. publications.iadb.org

- Public spending diversion. Governments spend heavily on policing, prisons, and criminal justice. That spending has opportunity costs: funds diverted from health, education, infrastructure, or anti-poverty programs that would more directly raise productivity.

- Investment and market confidence. High homicide rates deter both domestic and foreign investment. Investors price in political and security risk capital inflows shrink, and credit costs rise, raising the cost of doing business.

- Behavioral and social changes. Fear changes daily life: shops close earlier, tourism declines, nightlife shrinks, and entire economic sectors (restaurants, entertainment, culture) suffer. These behavioral shifts reduce aggregate demand and slow urban regeneration.

Each of these channels is measurable and, importantly, cumulative. When violence becomes chronic, it shapes expectations and long-term decisions: fewer entrepreneurs start businesses, skilled workers emigrate, and cities lose their economic dynamism.

The geography of fatal violence

Latin America is heterogenous. Some countries have homicide rates comparable to global averages; others register rates many times higher. On aggregate, the region’s homicide rate sits well above the world mean an imbalance that concentrates costs in particular countries and cities. In the Americas, roughly half of global homicides occur in this region, and organized crime is a major driver.

But the economic pain does not map perfectly onto homicide rates. Take Chile as an example: even relatively modest increases in violent crime there have produced outsized economic fallout because the country’s economy, public perception, and institutions historically depended on low crime levels. Recent research shows Chile’s rise in homicides has cost the country an estimated billions per year, forcing business closures and lowering consumer confidence. That outcome shows how fragile gains can be when safety deteriorates.

Organized crime, illicit markets, and the homicide-growth feedback loop

Homicides in Latin America are often not random acts of violence but outcomes of organized crime: drug trafficking, extortion, illegal mining, and human trafficking. These illicit markets create concentrated, high-profit incentives for violent competition. Where cartels, gangs, or mafias vie for territory, homicides spike.

This creates a vicious cycle:

- Organized crime generates profits → those profits are reinvested (sometimes in local economies) → competition intensifies → violence rises.

- Rising violence increases the costs of legitimate business and undermines the rule of law → the formal economy weakens → illicit markets become relatively more attractive.

- Weak institutions struggle to respond effectively, allowing criminal governance to fill gaps, which legitimizes parallel structures that further entrench violence.

Breaking this loop requires more than policing: it needs economic alternatives, judicial reform, and social programs that change incentives for potential recruits into criminal groups.

Hidden victims: inequality, displacement, and lost futures

The costs of homicide are not evenly distributed. Poor neighborhoods pay the highest price both directly (through victimization) and indirectly (through reduced access to opportunities). Violence exacerbates inequality in two ways: first by removing earning members from low-income households, and second by stunting the human capital of children who grow up in high-violence environments.

Moreover, homicide and insecurity produce internal displacement (families moving away from high-crime neighborhoods) and outward migration (skilled workers leaving the country). This “brain drain” further reduces growth potential and tax bases critical for public investment.

Policy lessons: what works, and what doesn’t

There is no silver bullet. Countries that have stabilized homicide rates and reduced crime costs used combinations of strategies rather than single interventions. Some lessons from regional experience and international evidence:

- Targeted law enforcement, not blunt force. Mass arrests and heavy-handed operations can temporarily reduce violence but may weaken the rule of law and provoke human rights backlash. Better results come from intelligence-led policing that targets criminal leadership and dismantles financial flows.

- Criminal justice reform. Efficient courts, faster case processing, and anti-corruption measures increase the probability of conviction which raises the cost of crime. Without credible prosecution, arrests are symbolic.

- Invest in prevention and opportunity. Programs that create economic opportunities, vocational training, and education in high-risk neighborhoods reduce recruitment into criminal enterprises. These are medium-term investments that pay dividends in human capital.

- Regulating and disrupting illicit finance. Money laundering safeguards, tighter controls on cash intensive industries, and cross-border financial cooperation cut off the lifelines of organized crime.

- Community policing and social trust. Building trust between citizens and police helps with information flows: neighbors are more likely to report and cooperate when they do not fear abuse or collusion.

- Regional cooperation. Crime crosses borders. Recently, a multi-country regional alliance launched by development banks and governments aims to coordinate intelligence sharing, tackle money laundering, and invest in joint programs a recognition that isolated national efforts are limited. Reuters

The politics of security: trade-offs and legitimacy

Security policies are political. Some governments have cut homicide rates through aggressive tactics that raise human rights concerns; other countries pursue rights-respecting strategies that yield slower but sustained results. Both approaches have political costs and benefits.

Public frustration over violence can also lead to support for populist leaders promising quick fixes, sometimes at the expense of democratic checks and balances. This choice can have longer-term growth implications: authoritarian or extrajudicial approaches can undercut institutional quality, weaken investor confidence, and create new sources of instability.

Measuring impact: from accounting to lived experience

Quantifying the full economic cost of homicide is complex. Studies aggregate tangible costs private security, health costs, loss of earnings and attempt to estimate intangible costs like pain, fear, and social cohesion. Conservative estimates focus on direct costs (the 3–3.5% of GDP figure), but the broader welfare loss lower educational attainment, worse childhood development, reduced innovation is harder to monetize and likely much larger.

In practice, the figure should be treated as a floor, not a ceiling: reducing homicides can free resources worth billions that, if reinvested, would accelerate human development.

Case studies: how context shapes impact

- Central America: Some countries have seen homicide declines following a mix of coercive measures and social programs; but dependence on extraordinary powers creates concerns about sustainability and rights.

- Mexico and Colombia: Both show how long-running conflicts with powerful cartels can distort national economies from agriculture to real estate and require multi-pronged responses that combine state capacity, anti-corruption, and international cooperation.

- Chile: A middle-income country that historically enjoyed low violence shows how small increases in homicide can have outsize effects on business behavior and public perceptions, illustrating why prevention matters even in relatively safer countries. Reuters

The investment case for peace

If violence costs the region more than 3% of GDP annually, the logical policy implication is stark: investing in reducing homicide isn’t charity it’s an investment with economic returns. Redirecting a fraction of the resources currently consumed by crime toward education, job training, judicial reform, and public health could yield higher growth than the same spending would in a low-violence context.

Donors and development banks have begun recognizing this, funding regional alliances and cross-border projects that aim to shrink illicit markets and bolster institutions. The opportunity is to pair fiscal investments with governance reforms so that gains are sustainable.

Conclusion: beyond statistics reclaiming potential

Homicides in Latin America are far more than headline tragedies: they are institutional failures with economic fingerprints. The human toll is irrecoverable, but the economic consequences are policy-reversible if governments and societies commit to long-term, integrated strategies that marry security with opportunity.

Reducing murders is not simply a moral imperative; it is a foundational economic policy. The choice is clear: tolerate the status quo and accept slower growth and higher inequality, or treat security as part of the growth agenda and reclaim decades of lost potential.

The clock on lost growth is ticking. For Latin America, addressing homicide is not only about saving lives it’s about saving futures, cities, and economies.